viewpoints on art

we, like flowers

emerging

once microscopic

to bloom

with patterned motion

intertwined

ubiquitous uniqueness

One can think about art in many ways. What do you see, what did the artist intend, what do others see? What is the meaning? As many have said “what you see depends on where you stand”. Here I look at one work of art and think about what the artist might have intended and then take the standpoint of buddhist Dhamma. Any object, image or photograph, even of the “mundane”, is much more than it appears. In fact every moment, every space, every thought, every one is unique. Here is an example of some thoughts about just one work of art...

A work by Liu Xiao Xian called Our Gods features in the collection of the Art Gallery of NSW. Here I examine that work, the artist and his ideas. These are used to create an initial interpretative framework based on what might have been the artist’s intention. Then I examine the implications of an alternative viewpoint – that of a student of the buddhist Dhamma (Dharma Skt). This perspective provides an intriguing interpretation that reveals parallels with buddhist teachings and suggests a viewpoint on seeing art more generally.

The observer’s “viewpoint” is critical in discerning meanings in a work of art. This idea can be illustrated in the following quote from Mark Epstein made in discussion about the role of buddhism in psychology and contemporary art:

“The observer and that which is observed are both part of an interpenetrating reality, and what we do with our attention determines how we experience reality” (Epstein 2007, p. 181).

An art work, once brought into existence by the artist, has a kind of life of its own. This idea is very well observed in the following (as cited in Baas 2005, p. 53):

“In a mysterious, puzzling, and mystical way, the true work of art arises “from out of the artist.” Once released from him, it assumes its own independent life, takes, on a personality, and becomes a self-sufficient, spiritually breathing subject that also leads a real material life: it is a being ... [and] possesses—like every living being—further creative, active forces. It lives and acts and plays a part in the creation of the spiritual atmosphere.”

This quote is from a work by Peg Weiss on Kandinsky. Kandinsky also believed that a work of art has an Innerer Klang or internal spiritual reverberation or sound. The interpretation of meaning in art is a subjective experience and may vary from person to person depending on their perceptions. However, it is important to understand and take account of the artist’s intentions, particularly if they are seeking to make an explicit or implicit reference to a subject matter. Nonetheless, taking Kandinsky’s view, it is reasonable for a viewer to consider the work as having it own “life” and as being independent from the artist. Therefore the observer is able to overlay the work with personal ideas or experiences, and, alternative philosophies.

The contemporary artwork I have chosen to critique is Liu Xiao Xian's Our Gods. It contains both Christian and buddhist religious iconography. The artist has stated that he does not adhere to any particular religion. Rather he has been influenced by a European concept of Dialectical Materialism. Further, the artist has given only limited explanations of the chosen work. Given the artist’s statements about his works there are unknown limits on the extent to which an interpretation through buddhist concepts can be thought of as being intended by the artist. However, as Jacquelynn Baas has said in addressing buddhism and art:

“The relationship of Buddhism to contemporary art practice can be explicit, implicit, or the work may resonate with insights characteristic of Buddhism.” (Baas & Jacob 2004, p. 25).

It is the latter that I intend to explore – how the work resonates with key buddhist concepts – its buddhist "Klang".

1. "Our Gods"

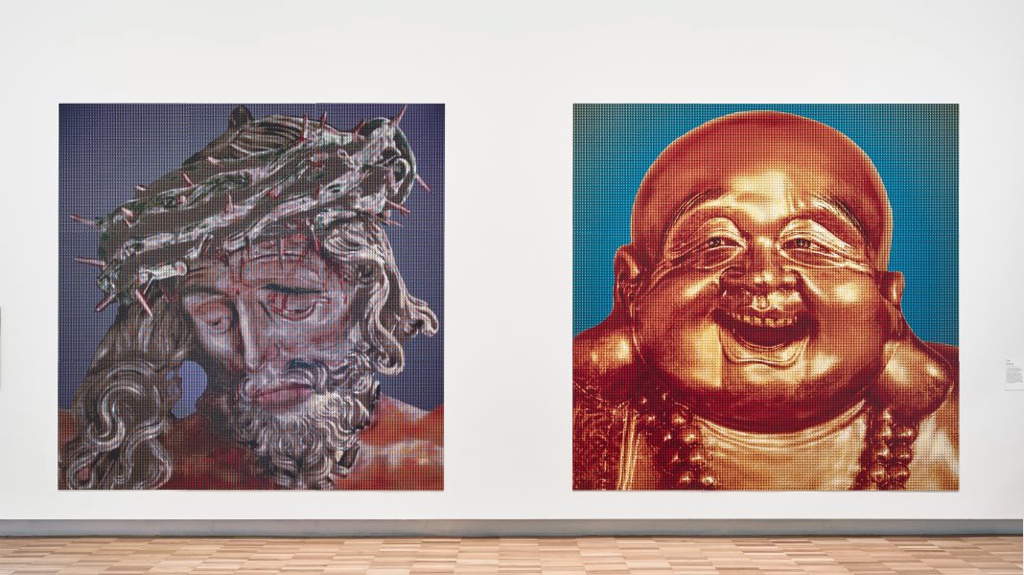

Liu Xiao Xian (1963- ): Our Gods, Art Gallery of NSW. Acquired in 2000. Image Source

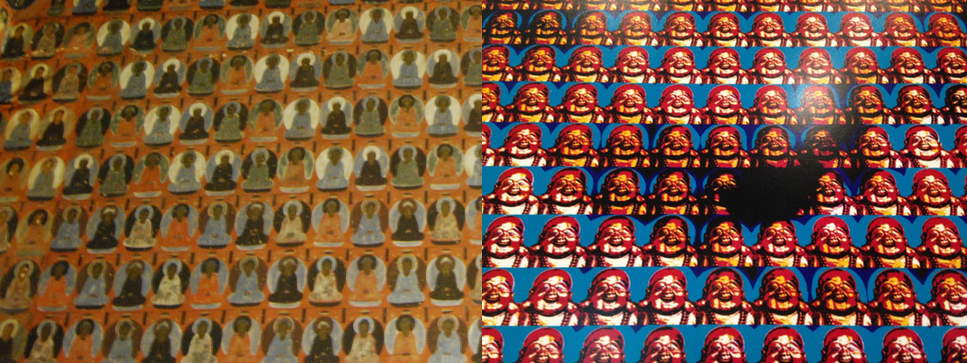

Our Gods is a large scale digital photographic work comprising of two religious icons. It is made up of 9 one metre square panels. Each large iconic image is made up of smaller figures of the other icon with a total of 22,500 smaller figures in each large icon (Menzies J ed. 2001, p. 180).

Importantly, the work is recent. It is not one where its original context or cultural milieu are largely unknowable; as it is for ancient art. Rather, it is in its intended context – that of a modern art gallery or similar large public space. Therefore it is reasonable to assume it has a reference point relevant to contemporary society.

The iconic images presented are common symbolic representations of their respective religious traditions: a crucified Jesus; and, a distinctly Chinese form of the Buddha – the so-called “Laughing Buddha”. The Laughing Buddha is derived from an eccentric Chinese Chán (Zen) monk (circa 907-923 CE) called Budai (Chinese) or Hotai (Japanese) after the “Cloth Sack” he carried. He is usually identified as an incarnation of the bodhisattva Maitreya – or the future Buddha. In folklore, he was said to travel and give sweets to poor children, and only asking for money from Chán monks and lay practitioners. Today he is one of the most commonly seen images of Buddhism. He is often seen in homes, temples, restaurants, businesses or jewellery as a bringer of good luck, good fortune and contentment. The vision of Christ is at crucifixion. At this moment his earthly body is said to have perished with considerable anguish. There are differing accounts of last words spoken by Jesus but the Gospels indicate a combination of desperation at being forsaken, and hope and confidence of resurrection in heaven. The representation of Jesus on the cross, or a crucifix alone, has become a common symbol of Christian beliefs in life after death and the divinity of Christ. Crucifixes are also often seen in homes or in jewellery etc. providing some "everyday" materialist parallels with Budai.

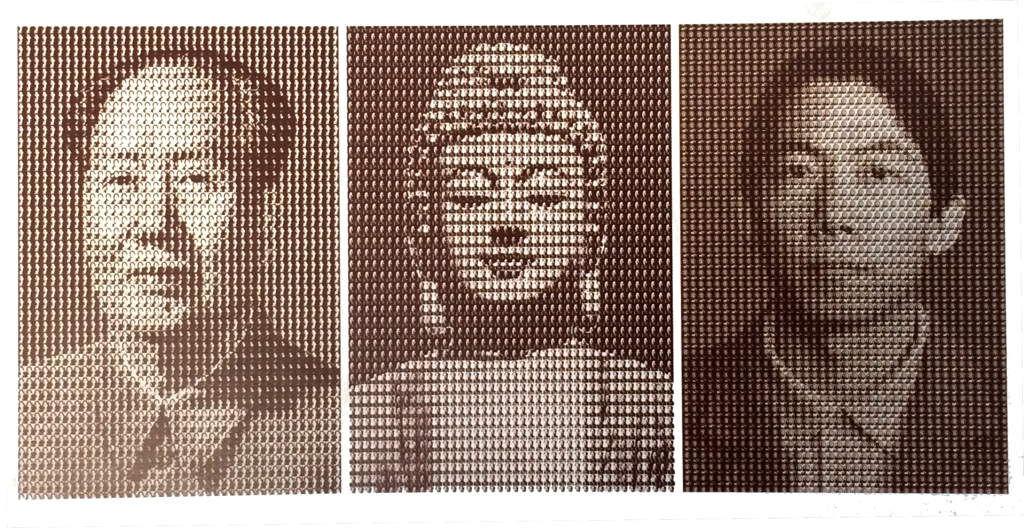

A recurrent theme in a number of Liu Xiao Xian's works is reincarnation and presence of a residual spirit after death. For example, on the work Reincarnation-Mao, Buddha & I, version II (Figure 2) the artist described the work in this way (RMIT Gallery 2009):

“Adapting the idea of reincarnation, this work speaks of the constant transformation of the cycle of life. The images of Mao – a political icon once worshipped like a god, Buddha – the icon of Buddhism, and myself, are used to explore the relation of a political figure, a religious icon and an ordinary man. Furthermore the delicacy of changes from the small scale to that of the whole may lead us into thoughts about micro verses macro.”

2. "Reincarnation: Mao, Buddha and I", version II, 2002

Liu Xiao Xian, Reincarnation: Mao, Buddha and I, version II, 2002, University Art Museum Collection, University of Queensland, Brisbane, courtesy the artist.

Reincarnation: Mao, Buddha and I is important to interpreting Our Gods as it uses a similar techniques, with one image being made up of small pictures of another. In explaining this method of construction of Our Gods the artist referred to a Chinese saying that:

“if you are inside a mountain you can’t see it, you have to go out of (the) mountain to see the whole image” (RMIT Gallery 2009, mp3 audio).

That is, if the viewer is close to one of the large icons and able to see the small images clearly, then they cannot recognise the whole image for what it is. But when you step back it changes into another image.

The Artist: “In-betweenness” and Dialectical Materialism

The Artist, Liu Xiao Xian, was born in 1963 in Beijing, and came to Australia in 1990 following the Tiananmen massacre in 1989. This event seems to have been pivotal in is decision to leave China. His art focuses on the cultural dislocations of being Chinese and living in Australia, a phenomenon he has described as “in-betweenness” (Roberts 2009, p. 221). In his interview with Claire Roberts he says the sense of in-betweenness came after he began travelling back and forth between Australia and China. It refers to his mind and heart being in neither China or Australia but somewhere in-between. This simultaneous outsider and insider perspectives gave him a new vision and interest in comparing his two cultures – Chinese and Australian – both their similarities and differences. Salman Rushdie is quoted as having said that: “The truest eye may now belong to the migrant’s double vision” (as cited in Clark ed. 2005, p. 11).

This is a consistent message about his art. As noted by Christine Clark, Liu Xiao Xian’s art practice investigates the experience of living “in-between two diverse cultures, to investigate the differences and similarities between his two worlds” (Clark ed. 2005, p. 46).

However, when asked about his own religious beliefs (e.g. in the Roberts interview) Liu Xiao Xian indicated he did not believe in an after-life, and only that his constituent matter will remain in a material universe. Further, as he grew up through Mao’s cultural revolution and he was heavily influenced by communism’s materialist ideology. There were no Gods or religion at that time, only Maoism. Liu has suggested his use of religious icons may be partly a reaction to that upbringing. He described himself as a “Dialectical Materialist” – a philosophy adopted as the official philosophy of the Soviet Communist Party. The ideas stem from work by Hegel, and were interpreted by Marx and Engels. Later Mao Tse-Tung introduced the philosophy into his own Communist ideology In an essay on the topic Mao quoted Lenin (Mao Tse-Tung 1937): “The law of contradiction in things, that is, the law of the unity of opposites, is the basic law of materialist dialectics. Lenin said, ‘Dialectics in the proper sense is the study of contradiction in the very essence of objects.’ Lenin often called this law the essence of dialectics”.

Among other things, this philosophy suggests that opposites can be identical and they are intimately interconnected with one another. Somewhat ironically for Mao and communism, the ideals of communism have recently been largely transformed into their own contradiction: capitalism as demonstrated by global economic success of modern China.

Despite the apparent seriousness of such themes in Liu Xiao Xian’s art, an important aspect of the artist’s work brought out in interviews is his interest in playful humour. His humour, with its irony and subversion raises a smile in the observer. This playful means of communicating important ideas is expressed as a desire for his art to operate at a higher level in the service of life. In that regard he has also quoted Mao Tse-Tung as having said: “art must come from life” and “art must be in the service of life” (as cited in Roberts 2009, p. 224).

What might the artist have intended?

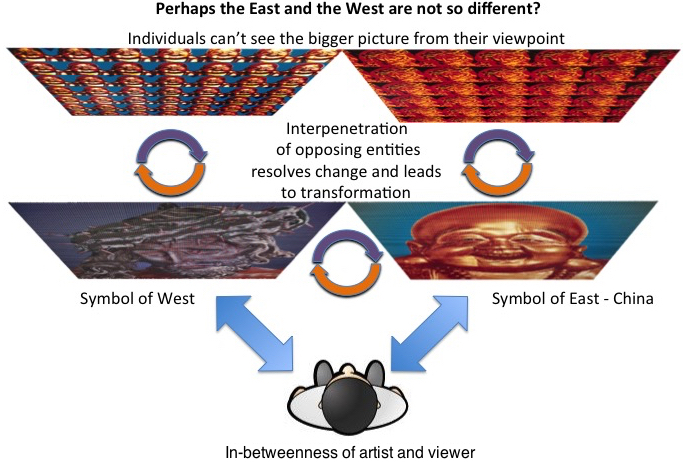

The observations above suggest that Liu’s works where large icons are made of smaller contradictory or contrasting figures draw attention to:

• similarities and differences between the two religions; and Eastern and Western cultures and ideas more generally as illustrated by China and Australia;

• revealing underlying contradictions or opposing features within or between things;

• the phenomenon of transforming one thing into a potentially opposite or contrasting thing; and

• the macrocosm and the microcosm and how an individual’s perception is influenced by cultural and geographic location, and the artist’s “in-betweenness” viewpoint.

All these parameters in Liu Xiao Xian’s work are consistent with a Dialectical Materialist viewpoint with its focus on the unity of opposites; and, change being resolved by the interplay of opposing objects. Further, they focus attention on the advantage of, and new perceptions from, understanding both sides of apparently opposed or contradictory positions.

In specific comments made by the artist on Our Gods, Liu referred to drawing attention to similarities and differences between the two religious icons presented (RMIT Gallery 2009).

On similarities the artist referred the “teachings” of the religions. I suggest that the religions might be seen as similar in that in both cases both people the icons represent:

• appear to have been real historical human beings between 2000 to 2500 years ago;

• were the founders of a religion that religion remains alive today and both have millions of adherents;

• had teachings stressing the importance of loving kindness and compassion and set precepts and examples to follow to achieve a better world on earth;

• had similar concepts of transmigration after death and involve mediation between heaven(s) and earth by celestial beings such as angels or bodhisattvas; and

• ultimately provide a path to salvation and liberation from earthly suffering.

On differences, the artists own explanation emphasised the difference between “East” and “West” embodied in the icons. I suggest some differences between icons that emphasize this include formal visual aspects of the images and contrasts between the symbols themselves. The Christ versus Buddha dialogue presents contrasts including: • Poverty vs Wealth –a symbol of foresaken death contrasted with golden wealth; • Night vs Day – Christ in the colours of twilight and golden Maitreya in full sun; • Death vs Life – crucifixion contrasted by smiling Maitreya; and • Eternal Heaven vs Cessation of Saṃsāra – a single rebirth in heaven versus no further rebirth at all.

Each icon is just one manifestation or image of a complex character or “ideal” they represent. They are incomplete in themselves and not representative of the totality of the Deity, religion, or tradition. Therefore the contrasts and contradictions both within and between the icons.

Contrasts within might be termed “invisible” contrasts or contradictions as they are created by the choices made by the artist prior to execution of the work. That is, the choice of the particular iconic image, which selectively highlights only certain aspects of the deity. For example, Christ is shown in death not nativity, and as human not celestial, foresaken and not an image of a radiant redemptive Jesus, as seen in other icons. By comparison the golden Maitreya is offering wealth and happiness as a Mahāyāna Buddhist icon and is in contrast to other possible icons such as an emaciated Buddha.

This idea of “in-betweenness” is integral to the images. The work suggests that an in-betweener is able to see things about China (represented by the Buddha) or about Australia (represented by Christ) that may be invisible or unnoticed by locals.

As noted above the artist used a “man on a mountain” analogy to draw attention to microcosm (individual) and macrocosm (country or culture). So that in Our Gods the small Buddhas can’t see that they are part of Christ, and the small Christs can’t see they are part of Buddha. The small figures might be individual “people”. The bigger picture is unknown to the individual “participants”. The bigger picture can only be seen by movement away from the plane of the image. That is, a Chinese person or an Australian cannot really see the system they are within, while they are in it. They can only see it clearly from an outside viewpoint. And then, if they do take a new viewpiont, the resulting transformation might not be what they expected. In short the work Our Gods invites the viewer to experience being an “in-betweener”.

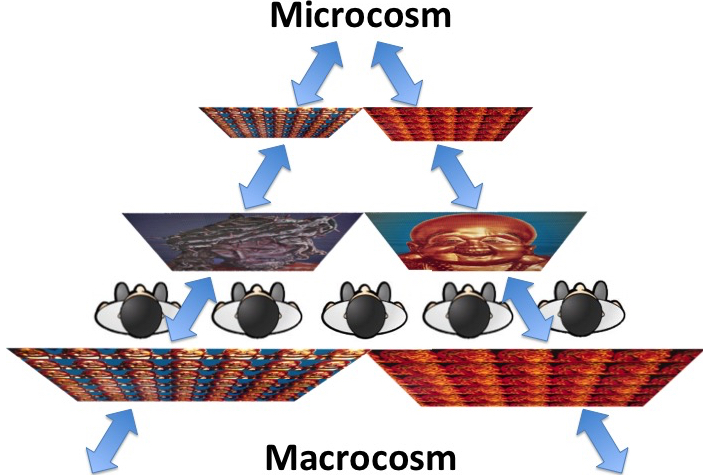

Figure 3 attempts to illustrate some of the main concepts the artist may have intended.

3. In-betweenness in macrocosm and microcosm

Source: author

This review of the work and the artist’s possible intentions suggests “viewpoint” is crucial to interpretation. It can be argued that if there is no evidence that the artist had an intention to portray a particular concept, then a critical review should not over-interpret the work. However, I argue that an individual viewpoint is valid based on their perception of the spiritual reverberations in a created work; in this case reverberations of buddhist concepts. There will, of course, me many potential reverberations for any given individual’s unique viewpoint from cultural, historical and personal events and beliefs.

4. Ten thousand (infinite) Buddhas

In buddhist art a dialogue between the work and the viewer is particularly important. There is a tradition of cultivating mental faculties with a focus on visualization, concentration and meditation. In this context artworks can be used as a focus for attention and devotion as illustrated by for example, Tibetan mandalas and thangkas. This is akin to the Indian concept of darshan, from the Sanskrit "to see”, where one can receive insight and visions from beholding a holy person or the portrayal of deities.

A personal viewpoint, in both micro and macro senses, reflects aspects of the individual and their personal interactions with the world and artwork. A personal starting point in a buddhist analysis is to view the work from the point of view of personal mental practices, such as mindfulness meditation, which is intended to raise awareness of internal and external phenomena. One of the four foundations of mindfulness (Satipaṭṭāna) is to experientially recognize the nature of the mind as a cluster of changing physical and mental processes/elements or dhammas/dharmas (Anālayo 2006). These processes, in common with all conditioned phenomena, have “three marks”: anicca or constant change and impermanence; dukkha or suffering and unsatisfactoriness; and, anatta or “no-self” where there is no immutable or unchangeable core in any phenomenon (e.g. Harvey, P 2013, pp 57-62).

Looking at Our Gods from this perspective, it resonates with the three marks of existence through the icons themselves and the people they represent; and, as a consequence of the interaction between the work with the viewer.

• anicca is illustrated by the impermanence of the icons themselves. The use of smaller figures means that there is a constant shifting from one to another as the viewer move to and fro.

• dukkha or suffering is illustrated by the suffering of the “Passion” of Jesus at his crucifixion. The golden prosperous Buddha is also made up of all pervading suffering in the form of an underlying mesh of Jesuses.

• anatta or no-self is inherent in the imagery as there is substantive “self” in either icon. The Buddha image is not wholly Buddha, nor is Christ wholly or immutably Christ. The icons transmute and shift from one to the other.

In Buddhist practice the purpose of recognising these marks is to assist the meditator to reduce grasping and attachment, which are key causes of suffering as expressed in the Four Noble Truths.

Also, the contrasting shift from Christ to Buddha and vice versa shows a dynamic transformation from “Passion” (in the Christian meaning of suffering) to “Dispassion” (or nibbida) and equanimity. Nibbida, is one of the processes a meditator can access to reduce attachment and the term refers to the “skillful turning-away of the mind from the conditioned samsaric world towards the unconditioned, the transcendent” (Access to Insight 2013).

The Mahāyāna buddhist tradition elaborated earlier teachings, in particular with the teachings of śūnyatā and nonduality of the conditioned and the unconditioned. As a consequence of these ideas every being would have within themselves “Buddha-nature” (tathāgatagarbha). That is, the seed of an awakened consciousness. Such concepts have influenced many branches of the buddhist tree, not least Chán or Zen traditions. The sūtra widely regarded as embodying these ideas is the Prajñāpāramitā or Heart Sūtra (Thích Nhất Hạnh 1988, p1):

The Bodhisattva Avalokita, while moving in the deep course of Perfect Understanding, shed light on the five skandhas and found them equally empty. After this penetration, he overcame all pain.

Listen, Shariputra, form is emptiness, emptiness is form, form does not differ from emptiness, emptiness does not differ from form. The same is true with feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness.

Hear, Shariputra, all dharmas are marked with emptiness; they are neither produced nor destroyed, neither defiled nor immaculate, neither increasing nor decreasing. Therefore, in emptiness there is neither form, nor feeling, nor perception, nor mental formations, nor consciousness; no eye, or ear, or nose, or tongue, or body, or mind, no form, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no object of mind; no realms of elements (from eyes to mind-consciousness); no interdependent origins and no extinction of them (from ignorance to old age and death); no suffering, no origination of suffering, no extinction of suffering, no path; no understanding, no attainment.

Because there is no attainment, the bodhisattvas, supported by the Perfection of Understanding, find no obstacles for their minds. Having no obstacles, they overcome fear, liberating themselves forever from illusion and realizing perfect Nirvana. All Buddhas in the past, present, and future, thanks to this Perfect Understanding, arrive at full, right, and universal Enlightenment.

Therefore, one should know that Perfect Understanding is a great mantra, is the highest mantra, is the unequalled mantra, the destroyer of all suffering, the incorruptible truth. A mantra of Prajnaparamita should therefore be proclaimed. This is the mantra:

Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha.

As part of his commentary on the Heart Sūtra Thích Nhất Hạnh invoked the idea of “inter-being” to explain that no thing, entity, object, thought or consciousness is an independent thing. Rather, things are explained by previous conditions and there is an interflow between the living and the non-living - a continuity and dependence upon the past. Inter-being reflects pervasive interdependence. Thích Nhất Hạnh used a metaphor of paper to illustrate that interdependence. For example: “So we can say that everything is in here with this sheet of paper. You cannot point out one thing that is not here—time, space, the Earth, the rain, the minerals in the soil, the sunshine, the cloud, the river, the heat. Everything co-exists with this sheet of paper. That is why I think the word “inter-be” should be in the dictionary. “To be” is to inter-be. You cannot just be by yourself alone. You have to inter-be with every other thing.”

So it is the same with art. The paper, the clay, the plastic, the metal, the pigments depend upon so many materials, people, places and events. The accumulation of technology in many forms, from coloured minerals on cave walls to modern chemistry and electronics. “Our Gods” is a modern digital photographic work, but when looked at deeply enough through the lens of Mahāyāna buddhist tradition it transforms. Despite its technology it has within it an infinite set of connections and interactions across a deep history.

The specific imagery used in “Our Gods”, particularly the way it draws attention to macrocosm and microcosm in repetition of deity images resonates with other aspects of the Mahāyāna buddhist tree. By bringing Buddhas into the cosmos through non-duality Mahāyāna traditions accepted that there were countless world-systems in the universe, and that Buddhas were as innumerable as grains of sand in the Ganges (Harvey 2013 p. 162). Each Buddha had its own “Buddha-field” or Pure Lands and they stretched across space and time.

A macrocosmic image of many Buddhas is found in many Buddhist temples and artworks. Indeed the idea of many thousands of Buddhas is visually reminiscent of, for example, the walls in the Main Temple at Nan Tien, or the paintings in the “Caves of a Thousand Buddhas” in Dunhuang (see Figure 4).

Challenged by the idea of micro and macro it is possible to imagine Liu Xiao Xian’s work extending further from the two-fold repetition. That is beyond the individual and country to the constituents of an individual and the wider cosmos. Such a viewpoint would place the observer not at the ultimate point of observing the artwork, but being also like one of a number of smaller figures in-between scales – part of an even bigger picture, as in Figure 5.

5. A bigger picture

Source: author

This is a somewhat fractal cosmology with an infinite reflection of the two icons within the universe of the artwork. This concept of infinite reflection has parallels in some Buddhist cosmologies and metaphysics. In particular, an intriguing parallel to this imaginative step can be found in the Hua-yan or “Flower Garland” school of Buddhism. This indisputably Chinese school of Buddhism was founded by a monk Du-shun (557-640) and systematized by Fa-zang (643-712). Their key text was the Flower Garland Sutra or Avataṃsaka Sutra. The legend of this Sutra is that the Buddha preached it immediately after his enlightenment, but the audience was unable to comprehend it. As a result, Buddha decided to preach “more simple Hīnayāna sutras” (Ch’en 1964 p. 313). This school held that the phenomenal world can be likened to a dream, where each individual’s world may be different. The Sutra says, “By the power of the perceiver and perceived, all kinds of things a born. They soon pass away, not staying, dying out instant to instant.” (Liu 2006, p. 255).

One of the most important philosophical contributions of the Hua-yan school in the area of metaphysics was the doctrine of the mutual containment and interpenetration of all phenomena (dharmas). That is, all dharmas are intimately connected and mutually arising. The Flower Garland Sutra depicts a world of lights and jewels where light passes through the jewels and is also reflected in every other jewel and so on until infinity. Fa-zang likened this to the jewel-net of the god Indra – Indra’s Net (Harvey 2013, p. 147) or a mirrored room (Ch’en 1964 p. 317). For example, in chapter 30 of Avataṃsaka, “The Incalculable”, the net of jewels is made explicit within the dazzling verse portion (Cleary 1993 p. 893):

In each of those rays of light Appear untold lion thrones, Each with untold ornaments, Each with untold lights, With untold beautiful forms in the lights, With untold pure lights in the forms; In each of those pure lights Also appear various subtle lights; These lights also radiate various lights, Untold, unspeakably many. In each of these various lights Appear wondrous jewels like mountains; The jewels appearing in each light Are unspeakably many, untold. One of those mountainlike jewels Manifests untold lands; All of the mountainlike jewels Manifest lands like this.

Reducing one land to atoms, The forms in each atom are untold; All of the lands atomized, each atom’s forms Are unspeakably many, untold.

This is a Buddhist conception of an infinite and holistic universe. One thing contains all other existing things, and all existing things contain that one thing. “Truth” (or reality) is understood as encompassing and interpenetrating falsehood (or illusion), and vice versa.

In terms of the imagery of “Our Gods”, the distinctions between the two icons disappears, they simply become like two manifestations within a whole picture.

This doctrine of interpenetration also influenced other East Asian Buddhist schools of Buddhism, for example the Japanese Shingon school and the Korean Buddhist tradition.

The artist, the viewer and the artwork are part of a network of interactions. Like a devotee of early Buddhism looking at a stone statue of the Buddha; and like us looking at “Our Gods”, what we see and understand is dependent on a viewpoint within our impermanent traditions, cultures and social networks. While “Our Gods” is arguably a non-buddhist artwork, when viewed from the viewpoint of the Dharma, its imagery resonates with buddhist concepts. But in a bigger picture it can be seen that the interpretation of all things is dependent on our own unique viewpoint. It is an abiding puzzle that the universe has an infinite and ubiquitous uniqueness changing from moment to moment. It takes determined mental effort to see that reality, and to break the bonds of 'ordinary' perception.

References

Access to Insight, 2013, A Glossary of Pali and Buddhist Terms, Access to Insight (Legacy Edition), viewed 19 May 2018, https://www.accesstoinsight.org/glossary.html.

Anālayo 2006, Satipaṭṭāna: The Direct Path to Realization, Buddhist Wisdom Centre, Selangor.

Baas, J 2005, Smile of the Buddha, Eastern Philosophy and Western Art from Monet to Today, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Bass, J & Jacob, MJ 2004, Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London.

Ch’en, K 1964, Buddhism in China, A Historical Survey, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Clark, C (ed.) 2005, Echoes of Home: Memory and Mobility in Recent Australia-Asia Art, Museum of Brisbane, Brisbane.

Cleary, T (trans.) 1993, The Flower Ornament Scripture, A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra, Shambhala, Boston.

Epstein, M 2007, Psychotherapy Without the Self: A Buddhist Perspective, Yale University Press.

Harvey, P 2013, An Introduction to Buddhism, Teachings, History and Practices, 2nd Ed, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Hạnh, TN 1988, The Heart of Understanding - Commentaries on the Prajñaparamita Heart Sutra, Parallax Press, Berkeley, California.

Liu, JeeLoo, 2006, An Introduction to Chinese Philosophy: From Ancient Philosophy to Chinese Buddhism, Blackwell, Oxford.

Liu, Xiao Xian, 2002, “12 April-12 May, 2002. Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, Parkside” -Colophon, Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, Parkside, South Australia.

Liu, Xiao Xian 2009, From East to West, RMIT University, Vic. viewed 19 May 2018, http://www1.rmit.edu.au/browse/Our%20Organisation/RMIT%20Gallery/Exhibitions/2009/Liu%20Xiao%20Xian:%20From%20East%20to%20West/ (link now dead).

Mao, Tse-Tung 1937, Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung Volume 1, On Contradiction, viewed 19 May 2018, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-1/mswv1_17.htm.

Menzies, J (ed.) 2001, Buddha: Radiant Awakening, Art Gallery of New South Wales, NSW.

Roberts, C 2009, In-betweenness: the Art of Liu Xiao Xian, Art and Australia 47, no. 2, pp. 222-225.

RMIT Gallery, 2009, Liu Xiao Xian: From East to West, ITS Web Publishing Team, Melbourne, Vic. viewed 19 May 2018, http://mams.rmit.edu.au/cs1ucltu4m10z.pdf (link now dead).

RMIT Gallery, 2009, Liu Xiao Xian: From East to West (mp3 audio), ITS Web Publishing Team, Melbourne, Vic, in three parts, part 1 viewed 19 May 2018 at: http://itunesu.its.rmit.edu.au/sites/default/files/itunesmedia/RMITArtistTalk_LiuXiaoXian_part1.mp3 (link now dead)