what Buddha might have believed

co-arising: a key concept

The concept of "dependent arising" is a unifying element of the buddhist system of thought. It is a highlight of the intuitive "mind science" developed, from around 2500 years ago, by the Buddha and the thinkers who followed on with his ideas and methods. It explains how the Buddha’s teachings on the path to release, karma/kamma and rebirth are related to the philosophical insights of suffering (duḥkha/dukkha), impermanence (anitya/aniccā) and “no-self” (anātman/anattā).

In this discussion I focus on the Theravāda tradition of Sri Lanka and South-East Asia. The terms used are therefore in Pāli, the ancient Indian language used in Theravāda scriptures. Theravāda “can be regarded as generally closer in doctrine and practice to ancient Buddhism as it existed in the early centuries BCE in India” (Gethin 1998, p. 1). Some variations to concepts found in Mahāyāna Buddhism will be mentioned where relevant.

three marks of existence

Source: Photo above was taken in 2015 at the National Museum of India, Delhi, "Wheel of the Dhamma" Sandstone circa 2nd Century BCE, Bharhut.

Buddhism’s primary objective is liberation from an endless cycle of rebirth in a world (saṃsāra) to an ineffable state of nibbāna. The world is characterized by pervasive suffering or unsatisfactoriness (dukkha). Everything in the physical universe, and indeed the human mind and body, is impermanent (anicca) and in a state of flux. Buddhism does not accept the idea of a permanent individual self or soul capable of transcendent liberation, instead it has a doctrine of anattā (no-self).

Taken together, this set of three fundamental philosophical insights of dukkha, anicca, anattā is known as the “three marks of existence” (tilakkhaṇa). The three marks are common to all “conditioned” things. Some commentators paint this as a pessimistic philosophical position of suffering, impermanence and disintegration, with no self or soul awaiting redemption and everlasting life. However, it can also be viewed in a positive manner, especially as a result of moral and ethical consequences for human behaviour. Rather than being pessimistic Buddhist doctrines can be seen as placing responsibility on one’s own efforts rather than an external supernatural saviour. Such personal efforts are encompassed in the concept of volitional action (kamma) and its results. Indeed, the category of the ‘supernatural’ does not exist in Buddhist/Indian systems as it is found in the West. Rather, there is a comprehensive map of existence and such elements, including Gods, have a defined place, role and limits. It is possible to explain and unify Buddhist philosophical insights, and the role of kamma and rebirth, within the framework of paṭicca-samuppāda. While there are various translations of this Pāli term it is commonly referred to as “dependent origination” or “dependent arising”. The latter, is used by Gethin (e.g. 1998, p. 133), and is also used in this essay. The Buddha explained the broad concept of dependent arising as: “When this exists, that comes to be; with the arising of this, that arises. When this does not exist, that does not come to be; with the cessation of this, that ceases” (Ñāṇamoli and Bodhi 1995, p. 927; MN iii 64). Dependent arising “could very well be considered the common denominator of all the Buddhist traditions throughout the world, whether Theravāda, Mahāyāna or Vajrayāna” (Boisvert 1995, p. 6). Along with the four noble truths “dependent arising” is held as a central doctrine of Buddhism. The Buddha is said to have realised the noble truths at the time of his awakening and dependent arising at or around the same time (e.g. Lamotte 1980, p.120-121). An understanding of dependent arising is equated with an understanding the Buddha’s teachings (Dhamma): “One who sees dependent origination sees the Dhamma; one who sees the Dhamma sees dependent origination.” (Ñāṇamoli and Bodhi 1995, p. 284; M i 191). Dependent arising has been and remains somewhat enigmatic. It has always been held as profound and difficult (Walshe 1995, p. 223; DN ii 55); and, it seems that dependent arising continues to be a contested topic of scholarly debate. In the Saṃyutta Nikāya the Buddha teaches dependent arising in two directions: arising and ceasing. It consists of twelve links or nidānas (literally “to bind down”) broadly meaning “condition” or “motivation”.

A circular “three lives” presentation of dependent arising

figure 1 paṭicca-samuppāda dependent arising three lives model

Source: https://alivebeing.com/resources/images/figures/da-figure-1-1440.jpg

In the arising order or going with the hair/grain (anuloma) dependent arising is as follows (Bodhi 2000, pp. 533–34; SN ii 1).

"Bhikkhus, I will teach you dependent origination. Listen to that and attend closely, I will speak …. The Blessed One said this: "And what, bhikkhus, is dependent origination? With ignorance as condition, volitional formations [come to be]; with volitional formations as condition, consciousness; with consciousness as condition, name-and-form; with name-and-form as condition, the six sense bases; with the six sense bases as condition, contact; with contact as condition, feeling; with feeling as condition, craving; with craving as condition, clinging; with clinging as condition, existence; with existence as condition, birth; with birth as condition, aging-and-death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, displeasure, and despair come to be. Such is the origin of this whole mass of suffering. This, bhikkhus, is called dependent origination."

Dependent arising can be illustrated in a linear or circular manner. Figure 1 shows a circular format based on the Tibetan “Wheel of Life” (bhavachakka) with twelve links on the rim of the wheel. An illustration of a Tibetan version from the Sera Monastery is shown below. Some scholars suggest this circular format is undesirable (Thanissaro 2008, p. 5). However, the circular layout has some advantages in that it can clearly illustrate “rebirth linking” involving kamma and consciousness. It also graphically displays the central role played by unwholesome roots (kilesa) of attachment (lobha), aversion (dosa) and delusion (moha). Figure 1 uses the “three lives” elaboration. An explanation of this is provided in Abhidhamma literature such as Buddhaghosa’s Visuddhimagga (Buddhaghosa 2010, pp. 592–678; Chapter 17). Links one and two are in a “past life” whereby ignorance or false knowledge sets the conditions for formations or pre-dispositions to arise. Links three to ten are said to be in the “present-life” commencing with the arising of consciousness and the mind-body, which in turn condition further links to “becoming” (link ten). Links eleven and twelve are “future lives” with birth, old-age, death and inevitable suffering.

paṭicca-samuppāda Tibetan bhavachakka

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tibetan_chakra.jpg P. Roelli [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], from Wikimedia Commons.

Many different understandings of dependent arising have been made by scholars of Buddhism, teachers and Buddhist schools partly because the formulation has a number of puzzling features [See End Note 1]. However, two main interpretive modes of dependent arising are evident: a macrocosmic viewpoint, encompassing “physical” rebirth and life in general; and, a microcosmic viewpoint emphasizing “moment-to-moment” phenomena of the mind and consciousness. Both perspectives are relevant to how kamma and rebirth relate to dependent arising.

The teaching of kamma integrates with dependent arising. Kamma means “action” and refers to the doctrine that actions in life lead to a corresponding result or “fruit” (vipāka). It is ethically charged as virtuous deeds of body, speech, or mind will produce positive results in the future (either in this life or subsequent lives). The term has a number of meanings in different Indian traditions (e.g. Buswell & Lopez 2014, p. 420). In Buddhism, kamma was redefined compared with earlier Indian traditions to place an emphasis on moral intention (cetanā) as a key factor in creating kamma (Bodhi 2012, p. 1768).

The Buddha said: "It is volition, bhikkhus, that I call kamma. For having willed, one acts by body, speech, or mind." (Bodhi 2012, p. 963; AN iii 415). Importantly the fruition of kamma comes about when conditions and time are appropriate, even though there may be a very long time delay. The goal of liberation in the Buddhist path (nibbāna) can be seen as liberation from the results of kamma. Kamma is a driver of the process of saṃsāra with the arising and ceasing of phenomena through dependent arising across all realms of re-birth. In some realms dependent arising may well be different in detail, but kamma still operates. Kamma and rebirth are also controversial areas for scholars, particularly as the mechanisms are not fully explained in the suttas. Interpretation of suttas is required but they seem to support its relevance to both viewpoints of physical rebirth and moment-to-moment processes; and, that it is a fundamental explanatory process.

The operation of kamma within dependent arising is shown in Figure 2. It illustrates that saṃsāra will continue indefinitely unless action is taken to cut off the defilements. The Visuddhimagga describes this process as a “triple round” of dependent arising (Buddhaghosa 2010, p. 672; Chapter XVII):

"With triple round it spins forever: here formations and becoming are the round of kamma. Ignorance, craving and clinging are the round of defilements. Consciousness, mentality-materiality, the sixfold base, contact and feeling are the round of result …. revolving again and again, forever, for the conditions are not cut off as long as the round of defilements is not cut off."

Further, the bhava suttas (Bodhi 2012, pp. 310–311; AN i 224 and AN i 225) provide an elegant summation of the arising of a “present life” that closely follows dependent arising’s logic and explicitly involves kamma. The Buddha said (with link numbers added in brackets):

"…for beings hindered by ignorance (1) and fettered by craving (8), kamma (2–7 i.e. old kamma and kammic results) is the field, consciousness (3) the seed, and craving (8) the moisture for their consciousness to be established in an inferior realm (10). In this way there is the production of renewed existence in the future”.

This formulation would apply to all three bhava realms in link 10: sensual (kama), pure form (brahma) and formless (deva). Whereas the “standard” 12 link process description would probably only apply in sensual realms. [See End Note 2].

A triple-round of kamma driving saṃsāra

figure 2 paṭicca-samuppāda triple round driving samsara

Source: https://alivebeing.com/resources/images/figures/da-figure-2-1440.jpg.

Buddhism proposes a challenging set of “three marks of existence”, traditionally in the order of suffering (dukkha), impermanence (anicca), and no-self (anattā). All three can be integrated into the framework of dependent arising.

The first mark is the notion of life as dukkha or suffering. This is not unique to Buddhism [See End Note 3]. The world is seen as a never ending cycle of death and rebirth (saṃsāra) to be escaped from. The most significant expression of dukkha in Buddhism is the central doctrine of the four noble truths. The truths have also been described in medical terms as the disease, the cause, the cure and the medicine (e.g. Gethin 1998, p. 59). Dukkha therefore corresponds to the first noble truth of the “disease”. The teaching of dependent arising can be viewed as a re-expression and more detailed explanation of the basis of the noble truths. That is, the first truth being a diagnosis as the Buddha said in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta: "Now this, bhikkhus, is the noble truth of suffering: birth is suffering, aging is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering; union with what is displeasing is suffering; separation from what is pleasing is suffering; not to get what one wants is suffering; in brief, the five aggregates subject to clinging are suffering.” (Bodhi 2000, p. 1844; SN v 421). For the uninstructed “worldling” (assutavā puthujjana) these are the inevitable eleventh and twelfth links of going with the grain (anuloma). The quote also illustrates the second truth, that the origin of suffering is based on a set of unfolding conditions of the mind-body that give rise to craving (link 8), clinging (link 9) and suffering in life. The third truth, that the suffering can cease though an unbinding process – with earnest striving in a pratiloma (against the grain) direction to root out defilements. Using a dependent arising framework such striving involves removing the first condition of “ignorance” (of not having the knowledge of how things really are) so that subsequent conditions do not arise. The fourth noble truth is a description of the practical way to bring about that striving for cessation of ignorance. Its focus is on three broad thematic areas: living with moral and behavioural virtue (sīla), using meditation practices (jhāna and vipassanā) and developing wisdom about the nature of the world (paññā).

The second of the three marks of existence is anicca, or impermanence. This refers to the coming into being and passing away of all conditioned phenomena, both physical and mental. A fundamental way of understanding impermanence is through dependent arising. The “standard” model of the twelve nidānas is not a chain of “causation”. Rather, it illustrates how phenomena can be explained as conditioned things that depend on preceding conditions. The chain needs to be seen as a set of components that do not have an inherent permanent existence. It is better to view them all as “processes”. Each step is a dependent transformation process and is dynamic and impermanent. There does not appear to be scope for anything permanent - no underlying fixed structure to material things or to personality or mind.

The third characteristic that all things, whether conditioned or not, have no permanent essence. They are selfless or anattā. Anattā includes both saṃsāra and nibbāna (Hamilton 1995, p. 52). A belief in the existence of a self or ātman was a key feature of early Indian thought [See End Note 4]. The concept of anattā distinguished Buddha Gotama’s philosophy from many of his contemporaries. At a general level, anattā is in accord with the framework of paṭicca-samuppāda where all things arise in dependence on impermanent causes and conditions. At a more specific level, an important example of anattā found in the Pāli Canon is the analysis of human beings as consisting of five aggregate constituents or processes (khandhas) [See End Note 5]. A realization of the characteristic of no-self based on the five aggregates is held as very important to awakening in the suttas and in meditation practice. For example, a sutta about the Buddha’s exposition on anattā (using the five aggregates as the basis) concludes “while this discourse was being spoken, the minds of the bhikkhus of the group of five were liberated from the taints by non-clinging.” (Bodhi 2000, p. 903; SN iii 68).

The five aggregates of clinging are not only relevant to anattā but also to rebirth. The terms used for the five aggregates are variously translated but are traditionally virtually always mentioned in the following order:

1) rūpa: body / physical form,

2) vedanā: feeling positive, negative or neutral,

3) sañña: perception / recognition / apperception: perceiving a new experience in the context of past experiences to create a new whole,

4) saṅkhāra: formations / fabrications / volition; and

5) viññāṇa: mind / consciousness associated with senses.

While the five aggregates may not have been intended to be a comprehensive description of a human being (Hamilton 1995, p. 55) taken together they constitute a classification of key processes and components of the whole mind-body seen as relevant to the achievement of liberation. The term khandha or aggregate literally means "heap" (Buswell & Lopez 2014, p. 828) and was explained by the Buddha in terms of heaps of rice grains. This simile indicates that they are formations or saṅkhāras and should not be seen as unitary entities nor as permanent.

The order of the list of the five aggregates, and the pattern of their inclusion as four of the five (except sañña) in the twelve links of dependent arising, have been matters for much scholarly debate. Boisvert examined the relationship between dependent arising and the five aggregates in detail. He suggests that the placement of the viññāṇa aggregate last in the list is consistent with traditional cyclic presentations; and hence consistent with its early appearance in dependent arising. This, among other things, is evidence for a strong link between dependent arising and physical rebirth cycles involving the aggregates (Boisvert 1995, p. 149).

Figure 3 illustrates how dependent arising can be viewed not only as a description of a physical rebirth cycle (by showing how a functional sentient being arises), but also, (by including the five aggregates), how a sentient being navigates its way through birth and subsequent moment-to-moment life experiences.

Taking the physical rebirth perspective first and using the traditional three lives perspective, links 1 and 2 reveal the conditions set by on-going ignorance of “how things are” and the impact of kamma on formations and patterns of consciousness. The nature of the rebirth consciousness has been subject to a variety of views across schools of Buddhism. These views include the concept of a “storehouse” or “foundational” consciousness (ālaya-viññāṇa) proposed by the Yogācarā school, and the Theravādin doctrine of the bhavaṅga – an inactive level of mind that is still present when no mental activity is occurring. Importantly, Buddhist doctrine has been very careful in the expression of such an idea so that it is not inconsistent with the doctrine on anattā or no-self [See End Note 6 on the “shadowy” transmigration process]. The arisen consciousness (link 3) then conditions the form of life and the arising of a mind-body (link 4). The formation of the mind-body is the joining of “consciousness” with a physical form made of four elements: fire, air, water and earth, in appropriate conditions of warmth and life such as a womb. The ground of consciousness provides the conditions for the arising of the mind-body, and, according to some accounts mind-body also conditions consciousness (Boisvert 1995, p. 130). This mutual conditioning of viññāṇa and nāma-rūpa is evident in the story of the awakening of the bodhisatta Vipassi (e.g. Walshe, p. 211; DN ii 33). The resultant mind-body provides the conditions for various characteristics shared by sentient beings to arise.

Dependent arising and the five aggregates

figure 3 paṭicca-samuppāda dependent arising and five aggregates

Source: https://alivebeing.com/resources/images/figures/da-figure-3-1440.jpg.

Such characteristics are the organs of the six senses and the corresponding six aspects of mind arise and differentiate. These saḷ-āyatana are five conventional senses plus mind (link 5). The sentient being is now able to contact the world through the senses by perceiving the corresponding sense objects (link 6). These set the conditions for interaction, which is initially reflexive vedanā finding pleasant (sukha), unsatisfactory (dukkha) or neutral things (link 7). Ironically, this simple capacity sets the ground for thirsts (taṇhā) to arise: wants, needs and aversions (link 8). This is a process where āsavas or festering karmic predilections are able to flow in. The being is subject to processes which move it to seek to attempt to maintain pleasant things or to turn away from dukkha. This is the process in which the five aggregates become the "five aggregates of clinging" (upādāna-kkhandhas). This is grasping (link 9), which can take a number of forms including false views about the “self”. This set of processes leads to a state of existence or becoming (bhava). In terms of physical rebirth in our sensual (kāma) realm these processes on the first occasion would take place in a womb. That is, from link 10, a new-born child would emerge fully replete with all the anuloma aspects of being a human. There is a sense of inevitability about going with the grain, for example, a newborn child cries and desires and seeks to avoid dukkha. However, despite all efforts to the contrary, its birth (link 11) will lead to sickness, age and death (link 12) and inevitable suffering.

The physical rebirth approach to interpretation of dependent arising involving the aggregates has an important implication. Since dependent arising links arise on the ground of a previous link then the five aggregates are implied as being present in all processes subsequent to nāma-rūpa. This view may solve some alleged conundrums about the process. For example, those who have taken a literal view of the links cite contradictions, such as why is vedanā a link while already existing in nāma-rūpa, or why is sañña not a link? I suggest that if one takes the view that all aggregates are present in all links after number four, then the specified terms in dependent arising may be the “dominant” processes involved. This point has been made by others, such as Stalker (1987, p. 66-67 citing de La Vallee Poussin in French). The absence of sañña as a link is explicable as its operation, say in taṇhā (craving) and upādāna (grasping), could have been taken as assumed; and, many processes in links 4 to 10 are themselves “formations” or saṅkhāra because they are “compounded” things.

Taking a moment-to-moment approach, one finds that a range of ideas need to be addressed. Such as what is meant by nāma-rūpa, and of the flow and contents of the operative mind. A mind-based view of dependent arising raises issues such as the constant change across mind states leading to a requirement for near simultaneity across links. Also, there is an issue in relation to links 10 and 11, where, instead of being the life of an organism, they can be seen as outcomes of momentary experience or kammic “results” arising from a momentary “becoming” (bhava). Some scholars support a reading of the suttas that the Buddha had no ontological purpose for dependent arising (Shulman 2008, p. 306). Rather, it is to illustrate the operation of the mind from a humanistic perspective aimed at allowing people to learn how to bring an end to saṃsāric existence (Hamilton 1996, p. 195). Hamilton (1996 p. 135) also suggests the key is to understand nāma-rūpa as referring to the abstract identity of a being dependent on ignorance and that “life has conceptual and formational individuality”. In the mind-based model craving or taṇhā is a key source of dukkha. It suggests beings are driven by desires and fears from vedanā. This conditions responses in terms of clinging and seeking stability in life. That in turn conditions what we become and how we behave (bhava). So that, within a single moment those reactions give rise to a new “birth” of thought. That new thought and concomitant mental processes are subject to an end – a “death”. That death can often be painful or unsatisfactory especially if the thought processes were pleasant. But new processes arise again as a consequence of an underlying condition of a lack of clear knowledge of how things really are (avijjā). From the mental point of view, apparent personal continuity is explained by the connectedness of the processes of dependent arising.

Dependent arising, whether interpreted through the lens of physical processes/states or moment-to-moment mental processes simply indicates “how things are”. It explains that all conventionally designated things are conditioned saṅkhāras. As a result there is nothing permanent (anicca) in saṃsāric existence and no permanent entity that might be called a “self or soul” (anattā). Further, there arises dukkha and the escape from this situation is liberation or nibbāna.

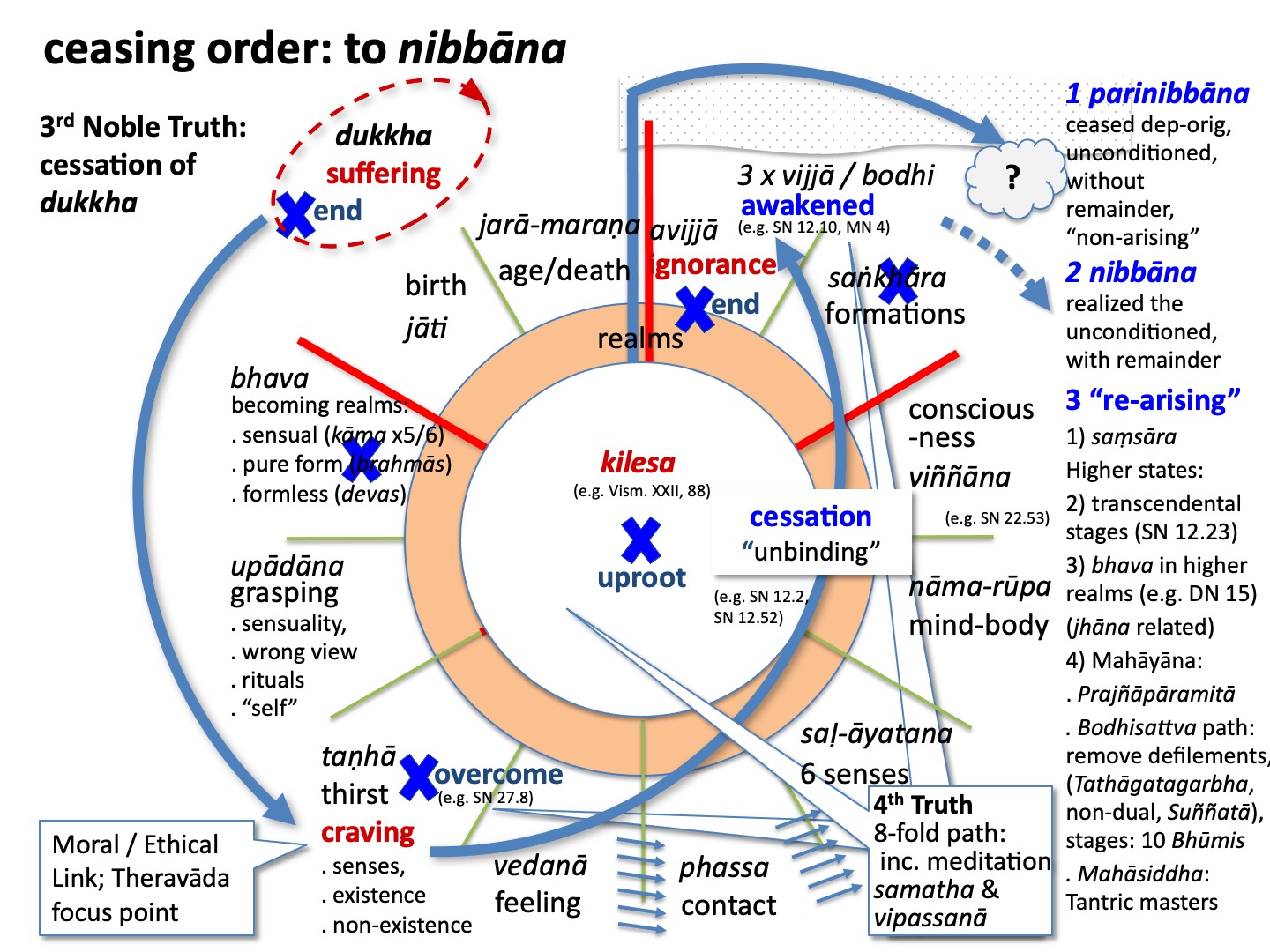

Nibbāna literally means “blowing out” (Gombrich 2009, p. 111) refers to cessation and is “unconditioned” (asaṅkhāra). The term nibbāna is as a metaphor to describe the state achieved when the internal fires of attachment, aversion and delusion go out (since it is by removing the "fuel" that one extinguishes the "fire"). In a number of suttas the Buddha uses the reverse or ceasing order of dependent arising as a means of explaining the progression towards putting out those fires. Nibbāna is the state entered into by the Buddha “awakened one”. It can be viewed as a mental phenomenon at awakening and the content of that experience; and as a state or unconditioned realm after death (Gethin 1998, pp. 75–77). Reaching nibbāna brings an end to dukkha and breaks the cycle of saṃsāra. Its achievement is the ultimate soteriological goal in all Buddhist traditions.

4. Dependent arising and nibbāna

figure 4 paṭicca-samuppāda dependent arising and nibbana

Source: https://alivebeing.com/resources/images/figures/da-figure-4-1440.jpg.

Taking a macro/physical view of dependent arising nibbāna is a process of unbinding consciousness from matter. The achievement of nibbāna is thus equivalent to freeing a purified viññāṇa from its attachment to rūpa. As the Buddha said (Walshe 1995, p. 179; DN i 223):

"Where do earth, water, fire and air no footing find?

Where are long and short, small and great, fair and foul -

Where are “name-and-form” wholly destroyed?

And the answer is:

Where consciousness that is signless, boundless, all-luminous,

That’s were water, earth, fire, and air find no footing,

There both long and short, small and great, fair and foul -

There “name-and-form” are wholly destroyed.

With the cessation of consciousness this is all destroyed."

Nibbāna is not thought of as a cosmological place like heaven and is not a physical place in space and time. It is “unconditioned” consciousness released from saṃsāra and so would seem to be beyond space and time. As such it would neither exist nor not-exist and might be considered as a continuing permanent state of pure potentiality beyond the universe [See End Note 7 for some notes on this speculation]. As Gethin (1998, pp. 76–77) would have it, it is an absolute, unchanging state standing outside the cycle of rebirth and of dependent arising.

In accord with a microcosmic or mental view nibbāna can be seen as the content of an experience of “awakening”. As a mental process that experience of nibbāna is described as a state of ultimate peace, bliss, and freedom from anxiety, anger, fear and suffering. In this context the mental discipline of meditation and the adoption of the eightfold path are aspects of reversing the flow of causality and reaching back into the mind to a pure consciousness and the achievement of nibbāna. One can achieve nibbāna while alive, as the Buddha did, and a final nibbāna after death. Nibbāna achieved in current lifetime is called “nibbāna with remainder”. The term “remainder” refers to the results of a person’s past kamma that have not yet been extinguished – including the physical body. But in such a state an awakened one who has achieved the state does not accumulate any more kammic events throughout the remainder of their life (Harvey 2013, p.77). Once the effects of past kamma are extinguished the person dies and enters parinibbanā or nibbāna “without remainder”.

There are similarities and differences between Theravāda, Mahāyāna and Vajrāyāna traditions on nibbāna (Skt. nirvāṇa). There is common ground in that nibbāna cannot be characterized as either existence or as non-existence (Gethin 1998, p. 78). However, different paths are favoured. [See End Note 8 for a brief outline of variations in path].

In conclusion, the fundamental philosophical insights of Buddhist teaching (dukkha, aniccā and anattā) form an interrelated set of characteristics of existence. They have numerous linkages to other Buddhist doctrines such as kamma, rebirth, pervasive saṅkhāras such as the five aggregates; and, the four noble truths. A framework to integrate all these concepts in a holistic doctrinal view is the flexible doctrinal framework of dependent arising. Dependent arising can be interpreted from many viewpoints and appears to be a multi-layered, multi-timeframe and multi-purpose system. It can be applied in diverse ways to explain the Dhamma, the cause of suffering and the way to the cessation of suffering nibbāna. It can be a practical guide to meditators seeking to explore the workings of their own mind and it can be a cosmological guide to life, death and beyond.

End Notes.

NOTE 1 For some commentators dependent arising is a description of all that exists, whereas for others it refers only to mental phenomena (Shulman 2007, p. 299). [Note: As some scholars would suggest there can be no apprehension of the “world” except through consciousness and the mind any difference between such positions might be regarded as debatable]. Dependent arising can be viewed as relating to the arising of phenomena in consciousness in a single moment, or across multiple time periods or lives. Williams (2000, pp. 71–72) finds the twelvefold formula “strange” as it makes sense to “spread over three lives” yet it also looks like a compilation from originally different sources. Williams notes several problematic issues such as apparent repetition in the second and tenth links and the use of explanations involving kamma while no links mention it. Also, birth is not mentioned until the end, after a human personality has arisen. The distinction between becoming and birth is not clear. There also seem to be two different causes for rebirth ignorance and craving. The specific presentation as twelve links might be seen as a particular case of a more general principle that occurs in all realms other than nibbanā - which is unconditioned (Stalker 1987, p. 319).

NOTE 2 Some scholars (e.g. Jones 2009, p. 244) have suggested that in the suttas the Buddha did not explain the mechanism of the rebirth process or the workings of kamma, and canonical descriptions of dependent arising as a whole do not clearly mention kamma. However, there are several suttas that do involve kamma in the context of dependent arising, and they have important implications.

First, it seems the Buddha may have taken both macro and micro views of kamma using the closely related concept of cetanā or volition. In SN ii 65 (Bodhi 2000) the Buddha appears to takes a moment-to-moment approach saying: “Bhikkhus, what one intends … this becomes a basis for the maintenance of consciousness …. When consciousness is established and has come to growth, there is the production of future renewed existence” possibly emphasizing consciousness in the present. In the second (Bodhi 2000, p. 577; SN ii 66) this is re-phrased around rebirth as: “Bhikkhus, …. When consciousness is established and has come to growth, there is a descent of name-and-form” … and so-on though the chain of dependent arising. The latter can be seen as having a longer timeframe through consciousness descending into name-and-form (nāma-rūpa) across lives. Such descriptions of the arising of a state of existence can be viewed from either a “moment-to-moment” viewpoint as the basis for the continuation or repetition of mental states; or as physical rebirth.

The bhava suttas (Bodhi 2012, pp. 310–311; AN i 224 and AN i 225) provide an elegant summation of the arising of a “present life” that closely follows dependent arising’s logic and explicitly involves kamma. The Buddha said (with link numbers added in brackets) “…for beings hindered by ignorance (1) and fettered by craving (8), kamma (2–7 i.e. old kamma and kammic results) is the field, consciousness (3) the seed, and craving (8) the moisture for their consciousness to be established in an inferior realm (10). In this way there is the production of renewed existence in the future”. Speculatively, I would contend that the use of kamma to explain saṃsāra is a "generic" explanatory method, because it applies to beings in other realms (such as devas or brahmas) who may or may not have physical form (rūpa). A kammic formulation is used to explain existence in non-kama worlds. For example, in explaining existence in sense-sphere, form and formless realms to Ānanda, the Buddha says that there is kamma ripening in each case: "... for beings hindered by ignorance and fettered by craving, kamma is the field, consciousness the seed, and craving the moistures for their consciousnesses to be established in ...(a) realm. In this way there is the production of renewed existence in the future" (AN i 223-4, Bodhi 2012, p 310). The implication is that the twelve step processes only apply fully in sense-sphere worlds. Other variations of dependent arising - in detail - must therefore exist in other realms. An awareness of a disjuncture between early buddhist cosmology and the "standard" twelve links or nidānas may be a contributor to the variations in formulations of dependent arising observed in the suttas. That is, how "generic" the required explanation would be in relation to the audience or purpose of the Dhamma talk.

NOTE 3 Placing Buddhism in its historical context, the notion of life as suffering was a basic presupposition in the religious milieu of the time. It is difficult to ascertain the precise details of such early beliefs as various schools were later brought into the rather amoeba-like Brahmanical/Hindu fold. For example, the concept of Mokṣa does not appear in Brahmanical literature until the time of the Buddha with the Upanishads. While it is important to note considerable uncertainty about the diversity of this milieu, it is said that the Buddha initially followed ascetic Brahminical yoga traditions through his teachers, (e.g. Ñāṇamoli and Bodhi 1995; MN i 163). Early Brahminical yogins believed that their path led, through meditation, to the personal realization of ātman/Brahman (the ultimate transcendent “self” in unity with the universal “soul”). However, only at death would the achievement of their efforts be realized by liberation (mokṣa) and merger into the unity of the absolute. This was a “pessimistic doctrine - typical of the ascetic religions of ancient India where “existence in the world is bondage, and liberation is an escape from it.” (Wynne 2007, p. 62). The Buddha Gotama thus shared the view of the suffering of saṃsāra with his contemporaries. However, he differed in relation to the belief of an eternal self or soul ātman.

NOTE 4 A belief in the existence of a self or ātman was significant in the Vedas and Upaniṣads and continues into modern Hinduism. Those traditions had a different conceptual framework to Buddhism. Wynne suggests that for the early Brahminic yoga traditions cosmology provides the theoretical background to meditation. In life devotees pursued more and more highly refined states of meditative concentration (jhānas), quite possibly with the aim to simulate a reverse cosmogony towards Brahman. That is, going back to the absolute and in effect reversing the creation of the world. This would prepare the meditator for re-unification of their individual ātman with the cosmic Brahman at death (Wynne 2007, pp. 35–36).

NOTE 5 The aggregates were explained by the simile of a chariot in the Saṃyutta Nikāya: “Just as, with an assemblage of parts, the word ‘chariot’ is used, so, when the aggregates exist, there is the convention ‘a being’.” (Bodhi 2000, p. 230; SN i 135). The five aggregates are five groups or sets of “faculties or functions or processes” that help explain how our body operates. As “each khandha participates in the cognitive process” they allow us to understand saṃsāra and to see things “as they really are” (Hamilton 1995, p. 55).

NOTE 6 The Visuddhimagga for example describes the shadowy transmigration process as:

The former of these [two states of consciousness] is called “death” (cuti) because of falling (cavana), and the latter is called “rebirth-linking” (paṭisandhi) because of linking (paṭisandhāna) across the gap separating the beginning of the next becoming …. here let the illustration of this consciousness be such things as an echo, a light, a seal impression, a looking-glass image, for the fact of its not coming here from the previous becoming and for the fact that it arises owing to causes that are included in past becomings.” (Buddhaghosa 2010, p. 574; Vism 554).

In the context of Indian beliefs in the Buddha’s time the difference between a dead thing and a living thing was that a living thing has consciousness. This is illustrated by the Sāṃkhya philosophy where Jiva (a living being) is that state in which puruṣa (consciousness) is bonded to prakṛti (matter). Consciousness would be like a “life force” joining with matter in the womb. This is not to say that the evidence is overwhelming that Buddha specifically meant this, but the idea was part of the conceptual framework in India around the time of the Buddha. Especially relevant is that some scholars suggest that the two teachers of Buddha: Ālāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta were Sāṃkhya philosophers (Murti 1955, p. 60). However, the concepts of ālaya-viññāṇa and bhavaṅga might border on the “self” concept of ātman, which is not consistent with the Buddha’s philosophy. Dependent arising places the primary basis of bhava or “being” not as a soul, but as the joining of a conditioned rebirth consciousness with an appropriate physical form in an appropriate realm. The life form arising is based on the kamma carried over from previous lives and the saṅkhāras that arise from them. That is, throughout saṃsāric existence a cycle of rebirths takes place dependent on prior conditions and not upon a permanent self.

NOTE 7 In Buddha’s time achievement of an anattā state beyond the conditioned universe could also have meant a state above and beyond Brahman (as the universal soul). Perhaps, and very speculatively, I suggest the Buddha may have rejected his Sāṃkhya teachers and sought to go beyond the joining with Brahman after death that they aimed for (also see End Note 4). In a sense suggesting Buddha asked the question where does Brahman come from? The answer being, as I speculate, a state of pure potentiality beyond the universe - an eternal “source” beyond Brahman; beyond the achievements of the then jhāna masters such as those who were the Buddha’s teachers. However, while such a thought will have to remain purely speculative, I suggest it raises some intriguing interpretive possibilities.

NOTE 8 Three paths to awakening or buddhahood are generally recognized. First, is that of the disciple or hearer (śrāvaka), which leads to arahantship. For the Theravādins the arahant path is the ideal of Buddhist practice (Laumakis 2008, p. 66). Following the noble eightfold path, a person adopts right or appropriate views, intentions, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness and concentration. Through meditation the practitioner develops insight and comes to understand the three marks of existence (Gethin 1998, p. 193). A particular focus for Theravādins is taṇhā, which the Buddha identified as a key source of suffering (Ñāṇamoli and Bodhi 1995, p. 138; MN i 51); and hence it becomes a link in dependent arising that, when “broken” would facilitate the achievement of cessation. Second, the path of the paccekabuddha, or a solitary buddha who achieves awakening on their own without a buddha as teacher. A paccekabuddha is said to achieve liberation through contemplation of the principle of dependent arising (Buswell & Lopez 2014, p. 673). Third is the path of the bodhisattva leading to becoming a “complete and perfect buddha” (samyak-sambuddha). In order to become a samyak-sambuddha one must practice the ten perfections. This path characterises Mahāyāna traditions as articulated, for example, in the Lotus sutra. Vajrayāna Buddhism also recognizes the Siddha (perfected one) or Mahāsiddha (fully perfected one) as the “pre-eminent model of accomplished Buddhist practice” (Laumakis 2008, p. 66).

Bibliography

Bodhi, Bhikkhu 2000, The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: a new translation of the Saṃyutta Nikāya, vols 1 & 2, Wisdom Publications, Boston.

Bodhi, Bhikkhu 2012, The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: a translation of the Aṅguttara Nikāya, Wisdom Publications, Boston.

Boisvert, M 1995, The Five Aggregates: Understanding Theravāda Psychology and Soteriology, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Ontario.

Buddhaghosa, 2010, The Path of Purification: Visuddhimaga, translated by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu, Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy.

Buswell, RE & Lopez, D 2014, The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford.

Cox, C 1993, ‘Dependent Arising: Its Elaboration in Early Sarvāstivādin Abhidharma Texts’, in R.K. Sharma (ed.), Researches in Indian and Buddhist Philosophy, Motilal Banarisidass, Delhi.

Gethin, R 1998, The Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Gombrich, R 2009, What the Buddha Thought, Equinox, London.

Hamilton, S 1995, ‘Anattā: A Different Approach’, The Middle Way, vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 47–60.

Hamilton, S 1996, Identity and Experience: The Constitution of the Human Being According to Early Buddhism, Luzac Oriental, London.

Harvey, P 2013, An Introduction to Buddhism, Teachings, History and Practices, 2nd Ed, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Jones, DT 2009, ‘New Light on the Twelve Nidānas’, Contemporary Buddhism, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 241–259.

Lamotte, E 1980, ‘Conditioned Co-production and Supreme Enlightenment’, in Somaratana Balasooriya et al (eds.), Buddhist Studies in Honour of Walpola Rahula, pp.118–132.

Laumakis, SJ 2008, An Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Murti, TRV 1955, The Central Philosophy of Buddhism: A Study of the Mādhyamaka System, George Allen and Unwin, London.

Ñāṇamoli, & Bodhi, 1995, The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: a new translation of the Majjhima Nikāya, Wisdom Publications in association with the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, Boston.

Shulman, E 2007, ‘Early Meanings of Dependent Arising’, Journal of Indian Philosophy, no. 36, pp. 297–317.

Stalker, SC 1987, ‘A Study of Dependent Arising: Vasubandhu, Buddhaghosa, and the Interpretation of Pratītyasamutpāda’, PhD Thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Thanissaro, Bhikkhu 2008, The Shape of Suffering: A Study of Dependent Arising, Valley Center, Metta Forest Monastery, California, viewed 5 August 2016, https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/thanissaro/shapeofsuffering.pdf.

Walshe, MO 1995, The Long Discourses of the Buddha: a translation of the Dīgha Nikāya, Wisdom Publications, Boston.

Williams, P & Tribe, A 2000, Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, Routledge, London and New York.

Wynne, A 2007, The Origin of Buddhist Meditation, Routledge, London and New York.