a new Dhamma?

applied secular buddhism

"We cannot conceive of the birth of anything. There is only continuation. Please look back even further and you will see that you not only exist in your father and mother, but you also exist in your grandparents and your great-grandparents. As I look more deeply, I can see that in a former life I was a cloud. This is not poetry; it is science.... And I was a rock. I was the minerals in the water. This is not a question of belief in reincarnation. This is the history of life on Earth. We have been gas, sunshine, water, fungi, and plants. We have been single-celled beings."

Thích Nhất Hạnh (Ellsberg, Laity, Eds 2001 p62.)

This is a “Work In Progress” to test the idea of updating the buddhist Dhamma (Dharma) with scientific ideas from the life sciences. The terminology used is of Pali canon, the ancient Indian language used in Theravāda scriptures. Using this language is closer in doctrine and practice to early Indian buddhism this explores a modern interpretation of paticcasamuppada. Translating Pali and interpreting the technical words of the language remains problematic. The interpretations used here may or may not accord with those of other readers. For example, while I quote Thích Nhất Hạnh, his followers would likely disagree with me.

Contents

Introduction

Thích Nhất Hạnh is right about the interflow between the living and the non-living, and our continuity with the past. He coined the term “interbeing” to reflect this pervasive interdependence. Thích Nhất Hạnh’s demonstrations of, for example, the “creation” and “destruction” of paper, show clearly the continuity of matter and interdependence of existence. In buddhist terms it illustrates an aspect of dependent (co-)arising or paṭicca-samuppāda. The flow of matter between living and non-living is ever present. Every breath we exhale contains carbon atoms that were once part of our bodies, which came from parts of plants, animals, rivers, rocks and clouds. The atoms in our physical bodies are essentially the same as those that have existed on this Earth since its arising estimated at some 4.5 billion years or so (with some allowance for some subsequent inflows, outflows, decay and isotopic form changes). No doubt some atoms within me were once part of a dinosaur or an ammonite; and many other things besides. Our physical beings, and all other living things alive today are a continuation of ancestors. We have all been involved in recycling elements in structured, evolving and replicating configurations of networks, patterns, information and modular components since the origin of life here some 3.8 billion years ago. Life’s flux and continuation was intuitively grasped by the Buddha and ancient Indian philosophers. Formations or patterns arisen in the past (physical, mental, social), and their consequences, are perpetuated in the present. The expression of such intuitions may have been expressed in ideas including kamma and re-birth.

Today, many hold a “scientific” world view. Science can be seen as having somewhat more affinity with buddhism than other "religions". Perhaps this is because buddhism and science both see life and the world as arising from a set of contingent or dependent phenomena. That is, being as the result of processes that are somehow built into the fabric of the universe. The question of how or why the universe behaves that was is, of course, unanswerable. Many people also identify as “secular buddhists”. Taking this starting point, there is an interest in how we might reconcile ancient buddhist philosophy and its lessons for how to live one's life with science and our modern way of life. While buddhism may share an affinity, a number of "secular" buddhists reject the old concepts of kamma and re-birth. They do not see them as being required for a modern interpretation of the teachings (e.g. Batchelor 2017 or Smith 2018). One example is Batchelor 2012 p6 when he says:

“… with such key doctrines as rebirth, the law of kamma, and liberation from the cycle of birth and death …. The reason people can no longer accept these beliefs need not be because they reject them as false, but because such views are too much at variance with everything else they know and believe about the nature of themselves and the world. They simply don’t work anymore, and the intellectual gymnastics one needs to perform to make them work seem casuistic and, for many, unpersuasive. They are metaphysical beliefs, in that (like belief in God) they can neither be convincingly demonstrated nor refuted.”

Such rejections are also sometimes supported by quotations of particular texts, such as the parable of the raft, or the Buddha’s own exhortation in the Kālāma Sutta not to blindly trust doctrines without considering their consequences (e.g. Bodhi 2012, p281; AN i 191). Kamma and re-birth are seen as outdated and not relevant to our current cultural milieu. The 12 links of dependent arising are seen as obscure, repetitious or differently expressed in the texts. The focus of secular buddhism is on an interpretation to achieve the benefits of buddhist practices without any requirement for “belief” in a buddhist "religion" or it's “metaphysics”. So-called secular buddhism is directed at practices of meditation and the cultivation (bhāvanā) of buddhism’s clear ethical precepts and the eightfold path with responsible thought, speech and action. The alleviation of suffering is key, and not just for one’s own self.

However, I consider that kamma and re-birth do not need to be rejected from the model of dependent arising. Kamma and re-birth are a matter of perspective: whether one looks backwards or forwards; and, of definition. Some changes to the interpretation of these concepts are proposed as a way of reflecting the passage of ~2,500 years. In particular, our knowledge in the life sciences, such as genetics. Taking such a view means that changes can be applied to both a “physical” dependent arising approach (involving “re-birth” of a sort); and the moment to moment “psychological” approach. This proposal is compatible with views of many modern secular Dharma practitioners favour adopting a psychological interpretation only, which places nirvāṇa/nibbāna as a mental state rather than a physical one. It may also be compatible with the views of some "religious" buddhists, such as Thích Nhất Hạnh's concept of inter-being quoted above.

I have adopted an “agnostic” approach to this discussion. Some things about the world and the universe and either unknown or unknowable. For science, perhaps the largest “known unknowns” are dark matter and dark energy. For many other people, it is the nature of the soul or spirit. In scriptures the Buddha refused to give his understanding about things such as infinity, eternity, an afterlife or the existence of a soul, e.g. in the Cula-Malunkyovada Sutta (Ñāṇamoli and Bodhi 1995, p. 533; MN i 426 or Thanissaro 2013). This was akin to refusing to talk about the physics and cosmology of his day (for scientists), or the existence or not of a god (for theists). Rather, the Buddha emphasized the four noble truths and “unbinding” processes to become “awakened”. The Buddha thus seems to have wanted to provide truths about how to live life and ultimately how to transcend its difficulties within the conceptual framework of his time. The focus of an agnostic approach is on how modern eyes with scientific knowledge might see a version of dependent arising that is compatible with modern culture and world views.

Buddhist dependent arising

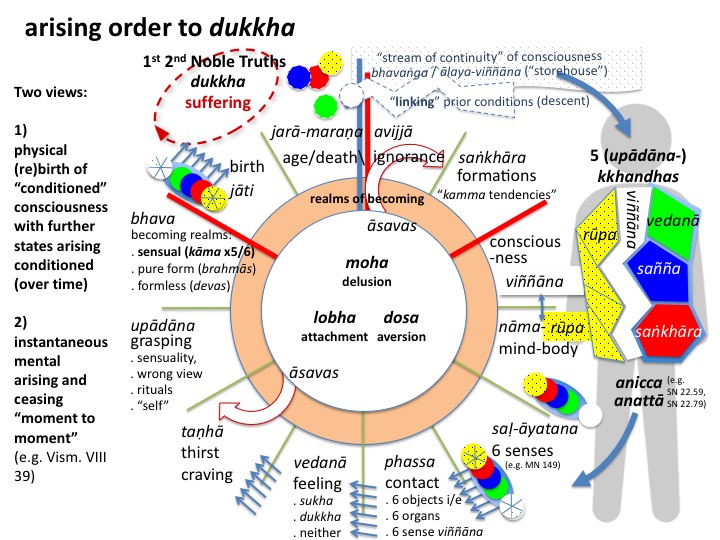

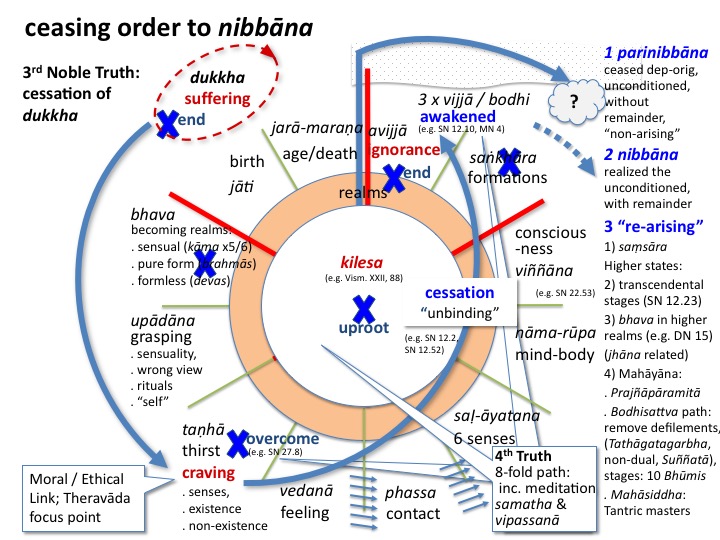

For Gotama Buddha the processes leading to awakening included knowing dependent arising: “One who sees dependent origination sees the Dhamma; one who sees the Dhamma sees dependent origination.” (Ñāṇamoli and Bodhi 1995, p. 284; M i 191). Dependent arising has 12 links or nidānas. These are processes. Each aspect can be thought of as dependent on its neighbour and may occur in a forward order (Figure 1) or reverse order (Figure 2) or be experienced as simultaneous or instantaneous (see also the main article here). In essence, everything is seen to be in flux based on "previous" and "subsequent" processes (can be viewed as simultaneous).

Buddhist dependent arising and ceasing: the “four truths”

figure 1 paṭicca-samuppāda arising to dukkha

figure 2 paṭicca-samuppāda ceasing to nibbana

Source: Figure 1 https://alivebeing.com/resources/images/figures/DA-F1-arising-to-dukkha.jpg. Figure 2 https://alivebeing.com/resources/images/figures/DA-F2-ceasing-to-nibbana.jpg

The arising order or “going with the flow” (anuloma) is shown in Figure 1. It explains the first two “Noble Truths” (suffering and its cause). The Buddha explained dependent arising as follows (Bodhi 2000, pp. 533–34; SN ii 1):

"Bhikkhus, I will teach you dependent origination. Listen to that and attend closely, I will speak …. The Blessed One said this: "And what, bhikkhus, is dependent origination? With ignorance as condition, volitional formations [come to be]; with volitional formations as condition, consciousness; with consciousness as condition, name-and-form; with name-and-form as condition, the six sense bases; with the six sense bases as condition, contact; with contact as condition, feeling; with feeling as condition, craving; with craving as condition, clinging; with clinging as condition, existence; with existence as condition, birth; with birth as condition, aging-and-death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, displeasure, and despair come to be. Such is the origin of this whole mass of suffering. This, bhikkhus, is called dependent origination."

Dependent arising, whether interpreted through the lens of physical processes/states or moment-to-moment mental processes indicates that all conventionally designated things are conditioned saṅkhāras. Saṅkhāras are literally “that which has been put together” or “that which puts together”. As a result nothing is permanent (anicca) in saṃsāric existence, there is no permanent entity that might be called a self or soul (anattā); and life involves inevitable suffering (dukkha). For Gotama Buddha the almost impossibly strong forward cycle of dependent arising would likely be seen as the eternal explanatory model for both the physical universe and the mind. It was as a result of dependent arising that living beings would continue to be born and re-born, and suffer illness, old age and death again and again.

In India, in Gotama Buddha’s time, re-birth and “transmigration” from life to life was accepted. A living being was believed to be the merging and combination of a form of consciousness with matter to create an animated nāma-rūpa (mind-body). The mind and the physical universe were considered to be inseparable. The specific life form in that next life was seen as a result of kamma from previous lives. The new mind-body would be in an appropriate form made of four elements: fire, air, water and earth, and occurred in appropriate conditions of warmth and life such as a womb. That life would also be in an appropriate “realm” (e.g. in one of 5 or 6 “sensual” (kāma) realms - depending on the buddhist vehicle: animal, god/demi-god, hungry ghost, human or hell). The realm would depend on the kamma stored in a somewhat mysterious ways such as a linking consciousness. There are also other “god-like” realms with pure form (of brahmās) or without form (of devas). There are important distinctions between the Brahmanical approach to this and the Buddha’s perhaps then “heretical” views. In Brahmanical thinking liberation (mokṣa) was a return to a universal soul (Brahman). For Buddha it was being beyond the conditioned universe (subject to dependent arising) in an “unconditioned” state called nibbāna.

In buddhist thought the way to end the eternal cycle was to reverse dependent arising as shown in Figure 2. However, the reverse order (pratiloma) or going “against to grain” is difficult. Reversing the pattern is the explanation of the third and fourth truths: how to end suffering and the nature of the path to reach it. They are a process of “unbinding” from the wheel of life and achieving nibbāna. Nibbāna literally means “blowing out” (Gombrich 2009, p. 111) refers to cessation and is “unconditioned” (asaṅkhāra). The term nibbāna is as a metaphor to describe the state achieved when the internal fires of attachment, aversion and delusion go out (since it is by removing the "fuel" that one extinguishes the "fire"). In a number of suttas the Buddha uses the reverse or ceasing order of dependent arising as a means of explaining the progression towards putting out those fires. Nibbāna is the state entered into by the Buddha “awakened one”. It can be viewed as a mental phenomenon at awakening and the content of that experience; and as a state or unconditioned realm after death (Gethin 1998, pp. 75–77). Reaching nibbāna brings an end to dukkha and breaks the cycle of saṃsāra. Its achievement is the ultimate soteriological goal in all Buddhist traditions.

It was by mentally manipulating dependent arising that one could extricate oneself from that eternal wheel. In the early buddhism (reflected in the Pali canon used in the Theravāda tradition) achieving nibbāna was, perhaps, to have one’s consciousness no longer cling or attach to matter. Nibbāna as an “unconditioned” state must lie “outside” the universe or at least not interact with it. A modern analogy of this would be like saying one becomes “dark energy” or “dark matter”, or “becomes” in another type of universe - not being observable to us. However, in the Mahāyāna tradition the situation is fundamentally different. The philosophy of Mahāyāna is that there is no difference between the conditioned and the unconditioned. Nāgārjuna argued, with seeming logic, in the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, that there was no distinction between conditioned saṃsāra and unconditioned nibbāna (Garfield 1995, p. 331; MMK 25.19-20). The reason being that both are “empty” (śūnyatā). This Mahāyāna buddhist concept means that one can experience of nibbāna in this world. This philosophical difference between Theravāda and Mahāyāna had profound impacts. Much thinking in the West about buddhist ideas (including secular buddhism) is influenced by both traditions and uses, sometimes eclectically, early Pali texts and later Chan/Zen or Huayan texts.

Figure 2 also illustrates three “types” of nibbānas (parinibbāna, nibbāna and other types that I have termed “re-arising”). The Mahāyāna tradition, and its philosophy emphasise bodhisattvas, who achieve nibbāna but “re-arise” in a saṃsāric world to assist other sentient beings’ achieve liberation. There are similar concepts of re-arising in other paths and traditions such as “transendental” stages or Mahāsiddhas. Such “post-nibbāna” re-arising experiences are akin to a “re-birth” in a psychological sense since the body would continue to exist. In modern terms, this might correspond to mental states achieved by meditation practitioners, which can have profound and lasting experiential impacts.

neo Dhamma

The proposition that there is no distinction between the conditioned and the unconditioned is attractive in the modern era. It allows nibbāna to be achieved in this universe, in this world and in this life. It also sits well with modern science where theory, for practical purposes, suggests this is our one and only universe. Perhaps today dependent arising can still be a model for helping people understand lived human experiences? After all, our minds are not so different from those of other homo sapiens just 30 lifetimes ago. Adopting the idea of dependent arising as a model for mental experience is similar to adopting other models of the mind like Freud’s (e.g. sub-conscious, ego, id) or Jung’s analytical psychology (e.g. collective unconscious). While such models have been superseded by modern neuroscience, they have, and remain, useful in assisting people to explore their minds and improve lives. They have helped set pathways towards modern cognitive-behavioural therapies. Likewise, buddhist ideas and mindfulness meditation have achieved great popularity as mental tools for stress reduction and well-being.

Perhaps dependent arising developed as an intuitive model, derived after much thought and meditation, to explain the operation of our mental and physical faculties. The original purpose of the model may be to provide a unifying framework for the Dhamma that embodied all its concepts; and, pointed to how mokṣa or liberation - the end of suffering - could be obtained by practitioners. So how can we include the concepts of re-birth and kamma as part of a “secular Dharma” (as Batchelor would have it)? Perhaps we can modify the definitions of kamma, re-birth and rūpa to take account of science. If we do the model of dependent arising can also be adjusted slightly to integrate new knowledge. But will it retain its integrity? The idea of retaining the concepts of re-birth and kamma in a neo Dhamma would have some advantages. For example, it means that ancient buddhist texts, such as those of the Pali canon, can be read with fluidity. No mental adjustments need to be held in mind that might obscure meanings, especially about dependent arising.

Re-birth

On re-birth, many people may be used to Abrahamic religions that propose an immortal soul that “comes into the world” for a period and will proceed “to another world” after physical death. Noting an agnostic view, I will set aside the question of a soul and leave its possible existence or non-existence aside. As Thích Nhất Hạnh observed, there is continuity of life on this planet. Looking back we see the all living things have been “reborn” many times in the continuous thread of life since it first arose. Re-birth then is a reality when viewed in retrospect, it is seen as a previous condition for the present. The life forms that exist today are survivors from many and varied previous ecosystems and of cataclysmic events. We arise as a result of our ancestors. This understanding is confirmed by modern science. It is likely that people have perceived this reality for centuries. It forms the basis of many belief systems that revere ancestors and our long chain of existence. At least from a purely physical perspective, rather than going to another world after death, our physical components will remain in this one. We will be reborn here - as Thích Nhất Hạnh observed, becoming part of many other things. To take this purely materialist view one step further, the implication is that every living thing is in its “last life” or last “inherited” life (to be agnostic). That is, while we have been continuously re-born over vast stretches of time, at any one point in time all beings that are alive will die and be “re-cycled”. Interestingly, taking this view means that after death we will be relatively “unconditioned” or in buddhist terms be in a kind of nibbāna right here on Earth. Knowing that every living thing (no matter how small or large and no matter what species) is in its last life means that they all deserve equivalent respect. We are all like leaves on a deciduous tree of life, we are all about to fall to the ground; and, to nourish the earth.

Kamma

Kamma can be defined as the results of “past and present actions”, or indeed intentions. Kamma is a reflection of our ancestors’ actions and intentions as embodied in us as their “survivor” offspring. “Old kamma” is inherited and acquired characteristics and behaviours through our “re-birth” from a long line of ancestors. We are here because of our ancestors behaviour, actions and physical structure and forms. Like us, ancient south asian people observed basic facts of birth, ageing and death and these needed to be fitted within their model of the mind and world. Anyone who has observed young sentient beings (whether human or animal) will know that they are born with unique with inbuilt personal tendencies, which affect actions in response to their broadly defined “environments”. I am confident that ancient thinkers also puzzled over the apparent inbuilt individualities of creatures and the complex nature of experience and the diversity of life on Earth. Early buddhists had great difficulty in coming up with a precise model of how old kamma might pass from one generation to another, and used a number of approaches by different buddhist schools such as the Yogachara school’s ālaya-vijñāna.

Now we now know about genetic evolution, and epigenetic and environmental influences on development. We have a well understood mechanism for understanding the transmission of what would have been termed past “kamma” through “re-birth”: the modern concepts of genetics and evolution. Among other things, living cells contain information about how to make proteins - key structural and biochemical components of a cell. The protein making instructions are encoded using three letter "words" in the form of Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Each cell of an organism contains a "library" of stored information. That information is read and expressed in a highly controlled or regulated manner, both in time and in space. The information is encoded similarly to a "text" containing a sequence of words intended to be read sequentially and selectively. It is organised into units known as genes, which can be likened to an individual "book" (a metaphor chosen to reinforce a similarity with texts and libraries). The total set of information in an organism defines its "genotype", which is broadly the contents of the library. The totality of the expression of an organism's genes, and the complex inter-plays between genes, gene regulation and other cells, leads to an overall composite outward appearance called a "phenotype". The expression of genes provides the basis for the operation of an "economy" involving the acquisition of resources and energy and their transformation into structures and movement, and releasing of wastes etc. The phenotype is defined, as the Macquarie Dictionary puts it: "the observable hereditary characteristics arising from the interaction of the genotype with its environment". The phenotype largely results from reading and using the books in the library in particular patterns. The study of this controlled gene expression is called "epigenetics". Information in the library books is subject to change by internal errors, rearrangements, sharing with, or acquisition from others (e.g. horizontal gene transfer).

Some changes in information are persistent and inherited by copying. This results in new forms, behaviours and outward appearances. These outward appearances allow selection by external factors. A further biological concept is the "extended phenotype" (Dawkins 1982). The extended phenotype includes behaviours and artifacts made by the organism, and explicitly connects the interaction with environment and all of an organism's characteristics - internal, external and behavioural. That is, the phenotype of a bird includes its body, behaviours and nest - and perhaps for humans, behaviour and “material culture”. Selection pressures operate on the extended phenotype. The selection process results in one or more forms surviving and/or being preferentially replicated in comparison to competitors and kin. Changes accumulate over time and two "species" can diverge from their ancestors - each with slightly different characteristics. The different phenotypic characteristics interact differently with the resulting in differential survival and reproduction rates of the two species. This is the basis of Darwinian evolution. As a result of such processes human beings experience a self and consciousness. Our bodies and minds are complex. Although hotly debated, perhaps consciousness itself has arisen (as an emergent property ) from the very complex structures and functions of life’s self-organizing systems and structures that have developed over aeons of time. As living beings we display an awareness of the surrounding physical environment and the internal environment of “self”.

Perhaps the “extended phenotype” is a useful analogy to the ancient intuitive perception about continuity in “re-birth” and kamma (initially old/past-life kamma)? That is, our ancestors observed that something complex was being transferred from generation to generation across all types of creatures which may include not only physical forms but also behaviours and artifacts. In the case of human beings our extended phenotype would also include the mind and the collective impacts of those minds, constituting a noösphere.

In terms of “new kamma” we all experience the positive and negative impacts of our own actions, or of trauma; and of the actions of others. Scientific disciplines in neuroscience and psychology have grown around trying understand the mental patterns, structures, processes and interactions of human brains and minds. A key aspect of the brain is memory, which might be viewed as the laying down of neural patterns of varying duration, in buddhist terms such things may have been termed saṅkhāras. So having been reborn with embodied old kamma, we are immediately subject to mental, physical, social, cultural and economic environments. Such influences themselves are perpetuated (reflecting “old kamma” they embody) and provide context for newly born sentient being’s new physic and physical development - i.e. its “new kamma”. The influence of such pre-existing entrenched, instinctive patterns can condition socially harmful consequences in the world. From biological, and ethical perspectives adjustments to the human minds and our fully extended phenotype may be required to enhance our species’ chances of long term survival as we evolve.

Rūpa

On rūpa we now recognise that there are more than four elements (94 naturally occurring) and that their nature is relatively fixed for long periods of time (after their creation in stars); and, they combine into complex structures through various bonds or interactions. There remains uncertainty about the fundamental nature of matter despite the “standard model”, and at the quantum level strange things for a macroscopic being seem to be possible. Strawson (2006) suggests that if one takes a purely physical (realistic materialist) view on the universe, then no matter can be wholly non-conscious in its ‘intrinsic’ or ‘ultimate’ nature. He suggests any realistic materialist must be a panpsychist. Panpsychism seems to be similar in concept to the idea of Brahman, and suggests that consciousness may be somehow inherent in the stuff of the universe. Others, of course, argue that consciousness is a emergent property of complexity, particularly of large neuronal networks.

Life certainly is complex; and, on this world at least, is constituted by mainly carbon-based structures with some curious properties including self-replication and “information” or pattern storage capacity. We also have an explanation of the “form” creatures take in this world. It is now known to be, at least in the purely physical sense, to be through evolution and the inheritance of form information passed on (in a recombined form) from ancestors as genetic and epigenetic patterns within a system that has evolved over billions of years. That is, the transmigration process is no longer mysterious. There is no need for an ālaya-viññāṇa or similar “seed” consciousness. We know that we are born of our ancestors, with a long line of ancestors reaching back to the dawn of life on Earth as part of a continuous flow of life on the Earth’s surface layers.

A modern perspective on kamma and re-birth would see them as physically embodied phenomena in specific patterns. These are saṅkhāras: our universe has literally been been put together and puts together new forms. These are largely embodied in the properties of rūpa or “matter”. They have evolved to make sentient beings with a mind (nāma) and with specific forms of consciousness (viññāṇa). So 2,500 years after Buddha, as a result of our a greater appreciation of the basis and complexity of life, we have an opportunity to re-visit old intuitions. In order to do so we need to redefine some of the concepts of dependent arising.

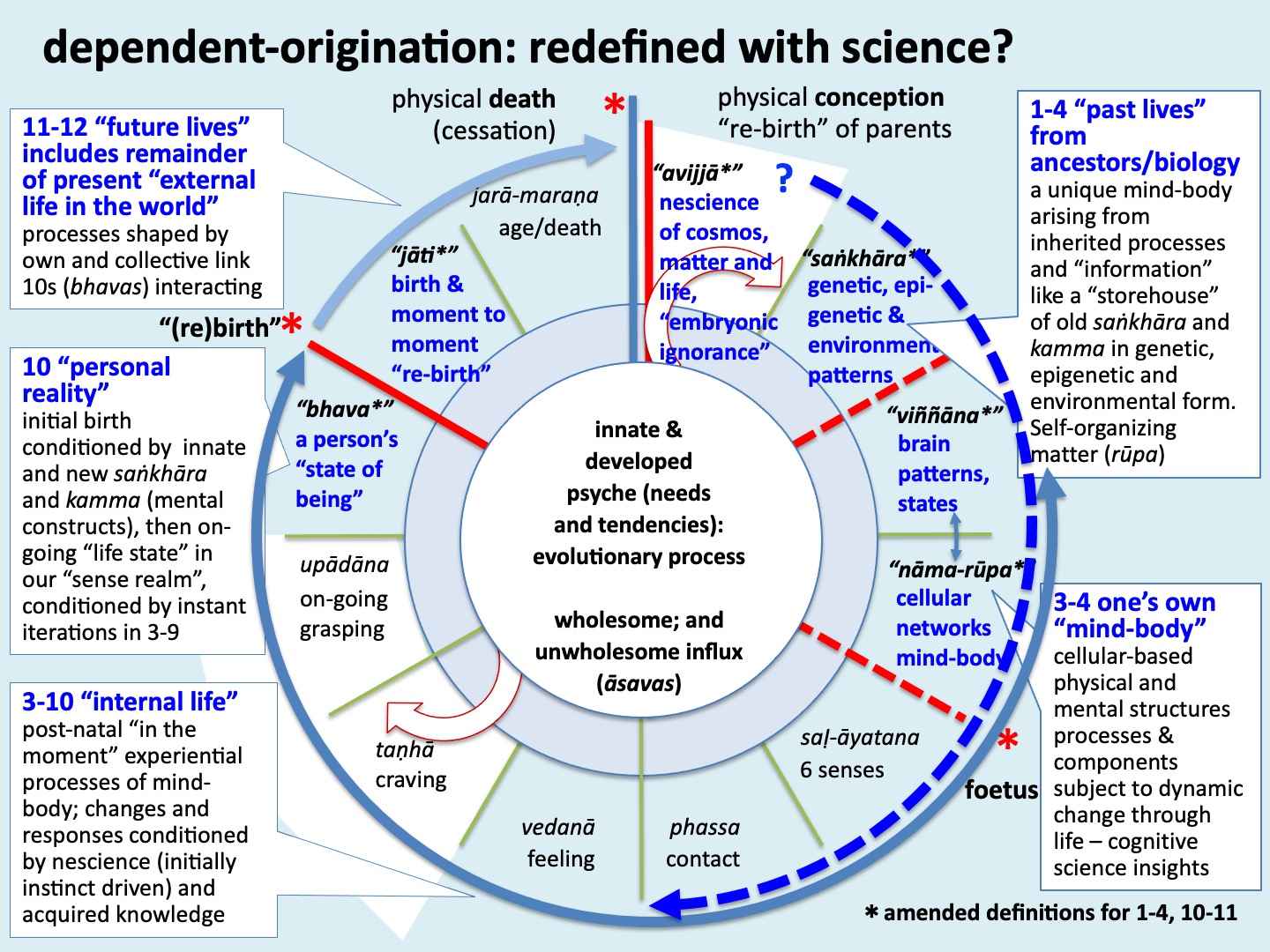

A "modern" dependent arising: some terms redefined

figure 3: paṭicca-samuppāda with some terms redefined for a scientific age

Source: https://alivebeing.com/resources/images/figures/DA-F3-modern-redefined-1440.jpg.

Redefined paṭicca-samuppāda

With the perspective of science, its knowledge of inheritance, cellular formations, encoded information, survival and adaptation, we can return to re-defining a model of dependent arising that some might find to be not so much at variance with everything we know. The redefined terms are set in the traditional “three lives” structure. That is, the first two links are conditions from the past, links three to ten are present conditions of experience meditated by the senses. The last two links are future oriented, but redefined to focus on an interactive life on this world. All aspects of this model have internal and external factors reflecting pervasive interdependence and impermanence. Buddha's concept of paṭicca-samuppāda is a theory of the emergent properties of consciousness - way before Aristotle. The Buddha's concept is useful in practice from a human perspective and to improve one's own life and that of others. However, it lacks 2000 years of thought and scientific advance. Nonetheless, it reflects and extraordinary degree of intuitive and experiential insight.

The past

Link one, an initial avijjā (ignorance), from a human perspective may be simply be the ignorance of a new-born child’s psyche with all its in-built and instinctive behaviours, but lacking knowledge and a full self-awareness. In physical and cosmological sense, with the arising of the universe there was the arising of matter. That matter is filled with potential and possible combinations. It becomes the ground or field of conditions for further arisings, but initially has simple forms. Further, as alluded to above, from a materialist panpsychist viewpoint the rūpa of the universe may have some kind of inherent basic potential consciousness? So perhaps, not unlike early Buddhists, this first link for us might reflect an intuitive sense of ill-defined yet necessary past conditions for the arising of our initially nescient consciousness?

Link two, shows us that the past structures the present through the Pali term: saṅkhāra. These can be formations, or that which is formed and that which forms. In a modern context, for living things the basic physical saṅkhāra of life are from genetics, epigenetics and innate behaviours. These represent the encoded inheritance of body and mind structures and formations from ancestors. There are many other saṅkhāras in the world we are born to, including landscape and environment; and, social, economic and power structures. With many structures in place the “extended phenotype” concept finds its expression as a “mass” or “heap” (in Pāli khandhas) of patterns. In the scientific view, similarly to that of buddhist dependent arising, the start of the “present life” is in large pre-determined by encoded patterns. The past-life saṅkhāra are therefore structures and patterns embodied physically in DNA/RNA/proteins etc as information about how the build a cell or multicellular organism. The saṅkhāra are also within in behavioural, technical and cultural patterns - the extended phenotype. Therefore “re-birth” and kamma have a modern interpretation. These links reflect biological “re-birth” through conception, it also represent “re-birth” of ideas and broader patterns through processes of self-perpetuation. Using a moment-to-moment approach saṅkhāra might be any of a number of mental patterns arising from one’s life. With the arising of form and structure there was the arising of self-replication, and the arising of life and organisation.

The “past-life” links 1 and 2 form the conditions for an inherited “present life”, or indeed life itself.

The present

Link three, viññāna (consciousness) arises from the complex cellular networks (also arising from forms of saṅkhāra) in the brain and body. It is intimately related to the development of our nervous system, the complexities of the brain, brain chemistry, neurotransmitters and the like. Perhaps, consciousness itself may arise as a result of the very complex structures and functions of life where self-organizing systems of structures (saṅkhāra) have developed over aeons to display an awareness of the surrounding physical environment and the internal environment of “self”. What is likely is that at least organisms with a nervous system have forms of consciousness.

Links 4 and 5 are about our bodies and minds, which biology and psychology now understand a little better. Link four nāma-rūpa (mind-body) has continued in microscopic form from ancestors (as cells within their bodies) and develops in-utero from a zygote to a largely pre-determined multicellular form. That is, the broad scope of a being’s physical form are set prior to its independent existence on Earth. That being will later develop and be “modified” through life. Perhaps then one’s “present life” is largely driven by in-built patterns, both physical and neurological (in the patterns of instinct for survival and reproduction) at least initially. After all, we obtain our existence from a very, very long line of survivors.

Links 5 through 9 are about the operation and experiences of our senses interacting with mind, including deep seated ancestral instincts. These links provide a useful experiential and conceptual model for exploration in meditation. Further, it is through these links that many modern secular buddhist ideas and practices operate.

The fifth link refers to the arising of the six sense-consciousnesses recognised in buddhism: the five senses of eye, ear, nose, mouth, skin and “mind” as a cognitive organ (mana). The mind in the meaning of mana is capable of perceiving dhammas, which were thought of as the elementary components of the mind; things such as mental states, qualities or properties. The identification of a “sixth sense” of “mind” is a powerful concept. Today many people ponder the nature of consciousness, and how it relates to the physical body. Thinking of the mind as a sense like touch and smell is intriguing. The ancient idea here is that each sense has a specific consciousness and specific sense “objects” that it perceives. The mind under this model was thought of having “mind objects” which that part of consciousness interacts with - specific dhammas such as the mental factors or cetasika (noting the multi-faceted use of the term dhamma). The sense organs, such as the eye interact with objects, such as say the colour “red”; similarly the mind sense interacts with special objects or cetasika, such as mindfulness, or delusion - thereby “colouring” the mind.

The following links six through to nine are mediated by these six sense gates and the objects to which they relate. This shows the importance placed on the mind in buddhism. In a new model it would show the importance of the brain and neuroscience. These links relate to the “internal” present life of a living being. This commences with the contact (phassa) between our consciousness and the external world and our own bodies mediated by all senses, including the mind (mana). These contacts lead to reactions (vedanā) and subsequent actions. Those actions are, at least initially, perhaps based on instinctive processes. In its natural anuloma flow contact, reactions and actions lead to on-going grasping (upādāna) in an attempt to avoid pain and seek pleasure or at leaset comfort and safety. It is here that modern psychology can assist us to understand the cycle from link seven "feeling", perhaps now termed "affect", to thirst in the buddhist sense, which is an unquenchable need, and finally to grasping or repeating the cycle. This process is very similar to contemporary theories of trauma recovery and "addiction". These lead to a person's bhava, or state of being - hellish or otherwise. This reminds one of the concept of "felt sense", or a bodily knowing arising from mindful attention that opens up. Attending to one's felt sense has been widely adopted for trauma therapy. This illustrates further how ancient experiential concepts in buddhism still resonate today.

Buddhism envisages innate āsavas arising from “unwholesome” tendencies (when uncontrolled) as infiltrating thoughts in this process. Overcoming of cravings (taṇhā) is crucial to liberation. The Buddha focused on taṇhā in his “first” sermon, the Dhammachakkappavattana Sutta: (Bodhi, 2000, p 1844, SN v 420) Buddha said:

"Now this, bhikkhus, is the noble truth of the cessation of suffering: it is the remainderless fading away and cessation of that same craving, the giving up and relinquishing of it, freedom from it, nonreliance on it."

In modern terms the unwholesome roots feeding taṇhā might be seen as “default” networks or instincts built in by genetics and embryology from evolutionary forces. In a contemporary world view it is through learning and socialisation that a young person learns about specific spacio-temporal constraints on behaviours such as social order and power structures. It appears that a modern interpretation can be that links 3-9 are about physical and psychic development process and the differentiation of sense organs and the perceptions that go along with them interacting with the external world and internal neural networks. The reactions and responses, positive or negative or neutral, lead - by going with the flow - inevitably to suffering and to defining our state of being or existence. That is, to link 10 “existence” or becoming (bhava).

Scholars and commentators consider that bhava can be interpreted in both cosmological and psychological ways. The Buddha did not define bhava, but used two agricultural analogies in the bhava suttas to describe it (Bodhi 2012, p. 310-311, AN i 223 and AN i 224):

"for beings hindered by ignorance and fettered by craving, kamma is the field, consciousness the seed, and craving the moisture for consciousness (or in AN i 224 “the moisture for their volition and aspiration”) to be established in a … realm. In this way there is the production of renewed existence in the future. It is in this way, ..., that there is existence."

Cosmologically it refers to existing in one of the five or six recognized “realms” for re-birth. To modern eyes, with an awareness of genetics, it may be sensible to take a psychological approach (noting an agnostic position on transmigration). As noted above the modern scientific view of re-birth is simply here on Earth. Psychologically it might be the state of mind of a person at any one time. Epstein for example, (1995, p.16 ff) in examining buddhism and psychology paints a picture of the mental states the six realms as aspects of the self:

1) hell as paranoid, aggressive and anxiety states (explored by Melanie Klein); 2) hungry-ghosts as unfulfilled cravings, that even when obtained give no satisfaction only more suffering like addictions; 3) gods as “peak experiences” (explored by Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow), pleasures, comforts and indulgence; 4) demi-gods as jealousy and competitiveness; the human realm as narcissism (refer to Winnicott and Kohut), but a realm with the best opportunity for Buddhist realization; and finally 5) animals, with instinctive gratification behaviours and desires explored by Freud, with the possibility of being stuck in an infantile state.

Such mental realms are not wholly internally determined such as those experienced by suffering trauma, perhaps at the hands of others, or who have addictive problems originating from external factors.

These analogies, can be read in physical and psychological ways. With a psychological focus, our consciousness develops through our actions and intentions, which are bathed in a soup of cravings. The generators of kamma are primarily intentions, thoughts and subsequent actions. These then lead to our current state of being. So perhaps a modern person would think of link 10 as primarily our “mental state of being” at a specific point in time.

Interestingly, there is a similarity between the buddhist idea of cultivation (bhāvanā) and ideas in other faiths, such as Christianity. That is, to undertake actions to alter one’s state of being to “become” (bhava) in a different manner. For christians this might be to become more like Jesus or God through, for example, practices as prayer, meditation and the cultivation of an ethical and moral life.

In the Pali canon, one of the main purposes of meditation was the allow on to see how things really are and end ignorance. That is, to see the three marks of existence: pervasive unsatisfactoriness (dukkha); a constant flux in the physical universe and impermanence (anicca); and no permanent self anattā. In modern terms these three seem to me to remain valid. Unsatisfactoriness could be a physical observation about entropy and time, or a model of human psychology with random reinforcement and addictive tendencies. Impermanence could be an observation about quantum physics and the continual flux of matter and energy in the universe. No-self might be a simple biological observation that the information we contain was a mixture of our parent’s information; and, that its expression varies across cell types in our bodies, and further that we cannot pass it on unchanged to our offspring. Our current information set is unique, re-organises and alters expression and is embodied in us for a limited period. Its specific components and properties cease to exist when we die (unless a genetic engineer intervenes!).

The future

The last two links (11 and 12) have presented issues for commentators and scholars as they appear contradictory to the preceding links. How is it that after “coming into being”, the next link is “birth”? One interpretation adopted to solve this is the three lives model that ascribes links 11 and 12 to “future lives”. In the context of a modern psychological interpretation of dependent arising where link 10 is our current “mental state of being” I think it intriguing to re-interpret these links as future life “in the world” - our social and interactive life.

Under this idea, at a point in time we would be experiencing our state of being (bhava), and from that “birth” and “life and death” might refer to the next transient mental and physical occurrence or interaction with the external world, society and other beings. That is, the moment preceding a “birth” in relation to the next moment; and that next moment’s life and death. This fits well with the buddhist doctrine of impermanence (anicca), and modern meditators views about moment-to-moment awareness. From a psychological point of view, the moment-to-moment becoming, rebirth and death leads to personal experiences, continuity and connectedness. Even if we were to adopt a physical interpretation of the “future lives” links it may still make sense. They would be seen as meaning the future lives of our genetic and other inheritances and our offspring - the people to come who will be influenced by the intentions and actions we make today.

Implications

What is the point of this speculation? Perhaps some people are are interested in buddhist ideas and their relevance to the modern world? Perhaps they are a little sceptical about the complex details and disputed ideas of Abhidhamma models? Is “buddhism” something to be accepted in whole or, if not, left behind? 2500 years ago Gotama Buddha and his followers engaged in an honest and thoughtful endeavour to better understand the world and “how” things are; and, to end suffering and live better lives. Today, we have 2500 years of hindsight on their extraordinary achievements, we have different understandings of life and the human mind. Might a new interpretation not only help improve the world, but also give buddhist concepts a new lease on life? Perhaps. Buddha’s intention and belief was that the understanding of dependent arising and practices flowing from it would assist devotees to achieve the soteriological goal of nibbāna - removing themselves from the saṃsāric world. Whereas today, the practices of sati (mindfulness meditation) and following aspects of buddhist teachings are intended to assist devotees adjust to the world.

Mental states induced by meditation are often seen today as desirable moments of clarity, joy and peace in generally turbulent lives. In Buddha’s day that would be seen as a mistake - an attachment and craving that would prevent liberation - revulsion and separation would have been a “better” experience. The point being that many modern people have already “re-interpreted” buddhism and its aims to suit their personal perspectives. Indeed, some have completely removed aspects of it, such as mindfulness meditation, into a modern context that is devoid of any buddhist ideas. Mindfulness meditation without a sense of purpose or a framework for why it might be useful is unlikely to be helpful in the long run.

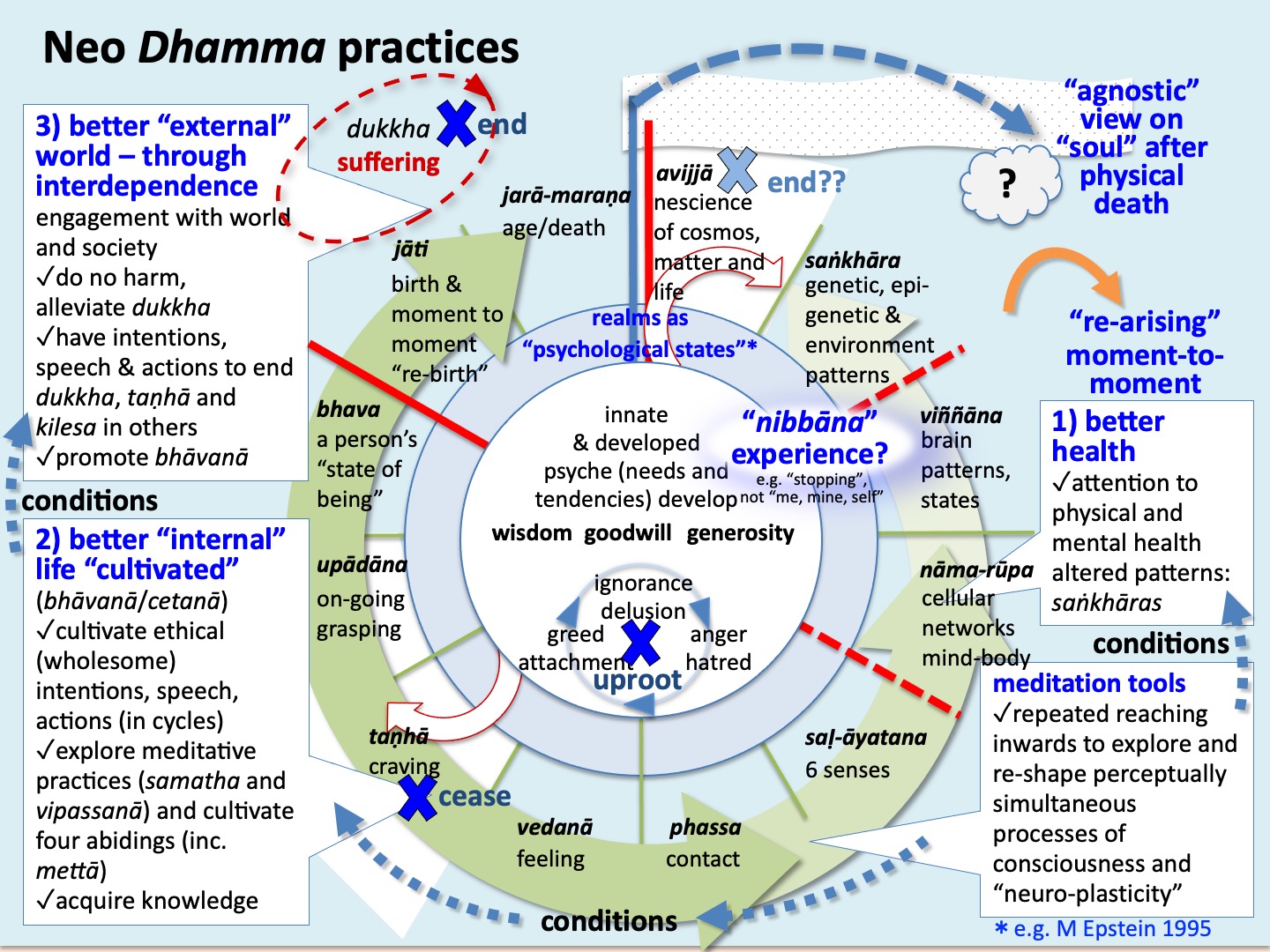

A neo Dhamma: practices in the context of dependent arising

figure 4: some implications of this modernized view of dependent-arising.

Source: https://alivebeing.com/resources/images/figures/DA-F4-modern-practices-1440.jpg.

We can use meditation tools to practice repeated reaching inwards to explore and re-shape processes of our consciousness. We might be able to achieve better health by attention to physical and mental health patterns and memories (saṅkhāras). The painful impacts of trauma on mental health might be viewed as generating harmful saṅkhāras, and, we might seek to unwind them. Meditation constitutes a repeated reaching inwards to explore and re-shape perceptually simultaneous processes of consciousness. It is conceivable that the concepts of “neuro-plasticity” apply to the impact of meditation, and that we can change who we are at deep levels. Nibbāna can seen as an “experience” and not a destination. A “stopping” of mind to experience not “owning” a thought or reaction. A stopping to gain a perspective on the illusion of a permanent self. That is, we can use repeated meditation practice as a tool for investigating experience, and being able to observe our reactions and responses both internally and externally. Batchelor (e.g. 2017 p98) describes a similar process with acronym ELSA: Embrace, Let go, Stop, Act. He says:

“One embraces dukkha, that is, whatever situation life presents, lets go of the grasping that arises in reaction to it, and stops reacting so that one can act unconditioned by reactivity. This procedure is a template that can be applied across the entire spectrum of human experience, from one’s ethical vision of what constitutes a “good life” to one’s day-to-day interactions with colleagues at work”.

Such practices then lead to the cultivation of one’s “internal” life (bhāvanā) or "state of being". In buddhist terms changes to intentions will flow (cetanā). But change is not easy - it goes against the stream. Like the Buddha’s agricultural analogies, it is like being a gardener, being aware of the seeds, the soil, the water and the weather. There is learning involved. Cultivating ethical and wholesome intentions, speech and actions, and overcoming the flow of dependent arising, requires cycles of practice. The tools of meditation practices (both samatha and vipassanā) can be used. We can explore the buddhist practice of cultivating the four abidings (brahmavihāras): loving-kindness, compassion, empathetic joy and equanimity. These and lovingkindness or mettā meditation in particular have the subject of recent interest (Salzberg 1995). Therefore, the meditation tools of buddhism should be seen as a delving back into the nature of our existences; and not simply as a health practice.

But an internal focus might be seen by some as selfish. Collective action is required to promulgate change. In buddhist terms this is the saṅgha - in a broad interpretation. Like traditional buddhism any new Dhamma would need to extend into the external interdependent world through engagement with society. The final two nidānas 11 and 12 are “future lives” birth, ageing, disintegration and death and I suggest we can interpret them in an external context. How do we improve our interaction with the external world in conjunction with cultivating our internal state of being (link 10)? All creatures and all life is interdependent and any person is interdependent with their world and society. We are thus talking about the interface between things that are both individual and collective. Perhaps the simplified statement of the Buddha’s doctrine given in the Dhammapada remains a good guide (Dhammapada, verse 183):

Not to do any evil, to cultivate what is wholesome to purify one’s mind: this is the teaching of the Buddhas

We need to cultivate intentions, speech and actions to end dukkha, taṇhā and uproot kilesa in ourselves and others.

A neo Dhamma? Practices and ethical actions

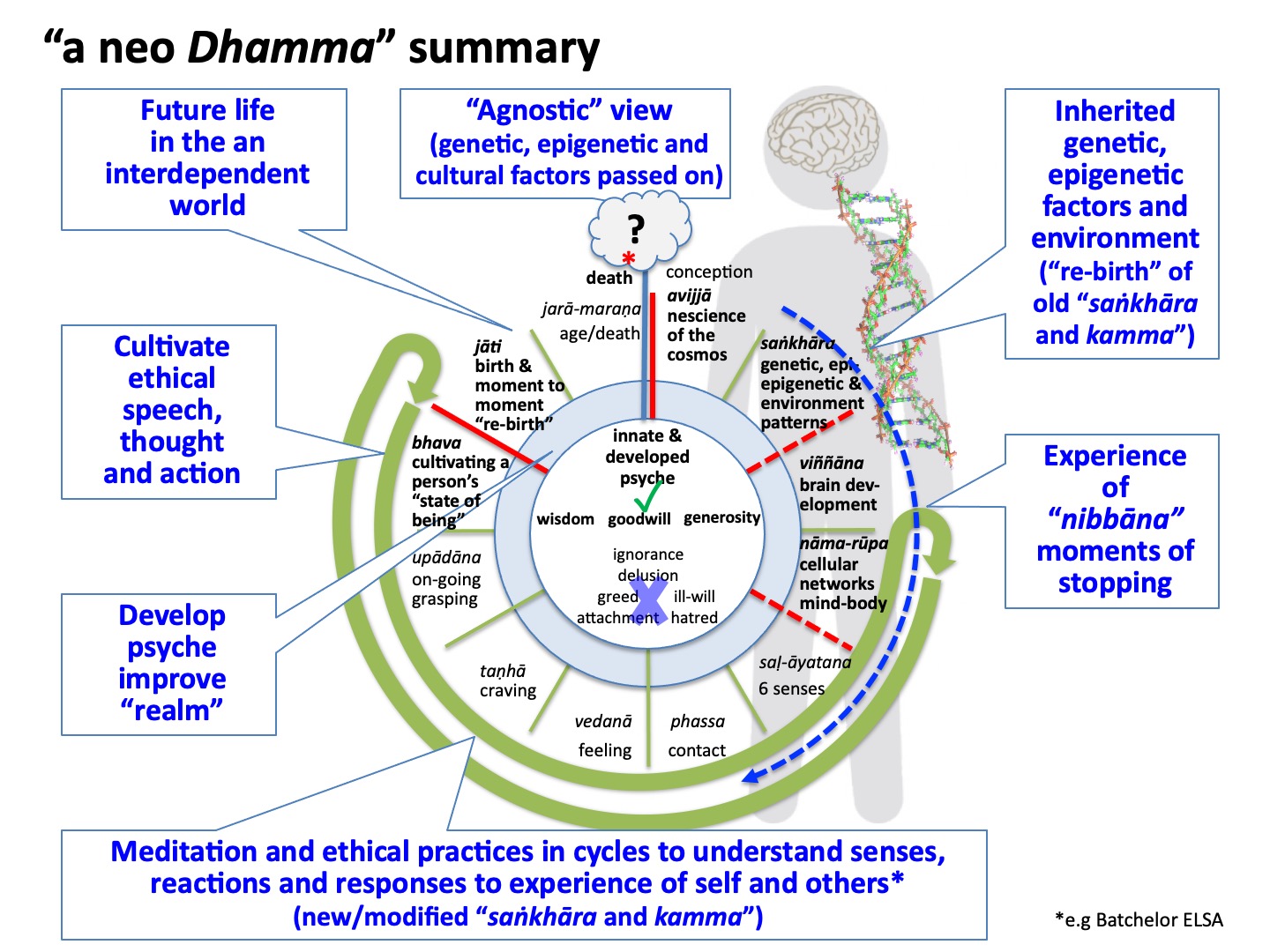

figure 5: a new Dhamma?

Source: https://alivebeing.com/resources/images/figures/DA-F5-neo-summary-1440.jpg.

Figure 5 provides a summary of this newly defined Dhamma. It incorporates dependent arising fully (albeit with some redefinitions). It allows us to place the buddhist project in a modern context. The main tools in box remain as they were: samatha (concentration) including jhānas and insight (vipassanā) including sati (mindfulness). Using these tools we can individually delve back into our cravings, feelings, perceptions, sense bases and consciousness to experience a kind of cessation either stopping or blissful peace - this is meditation. The seeker may be able to overcome trauma, reduce suffering, minimise unwholesome tendencies to free our consciousnesses and gain insights - this is the purpose of meditation. Experiencing and understanding these tools may or may not be of immediate assistance. But being aware of them, and having some, even modest experience of them may become important at some point in one's life - whether now or in many years from now.

When used appropriately such mental practices might improve our mental “realm” and cultivate a better “internal” life or "personhood". The challenge is to be our own gardeners and cultivate ethical wholesome intentions in both speech and actions. In ancient terminology this can generate good kamma (or reduced our “bad” kamma balance). In the modernised terminology here this can amend our internal mental store of memory patterns related to the results of our intentions and actions, which contribute to our current mental "state of being". Cultivation is not something that comes easily and practice and repetition in required. The recognition of delusions, aversions and attachments is not as easy as it sounds - delusions after all can be like impenetrable clouds. However, in opposition to the unwholesome roots (that are perhaps innate in us through evolution) are better things: wisdom, goodwill and generosity. I continue to believe that individual actions can lead to collective change.

Conclusion

Kamma and re-birth can remain included in a modern Dhamma. Viewed in retrospect they reflect a real past of genetics, epigenetics and behavioural inheritances. Our extended phenotypes (including the mind) and our networked society help generate new kamma (re-defined). That is, viewed in prospect our beings, thoughts and actions will be perpetuated for many generations - physically and mentally. Being aware that all living beings have evolved over aeons and we are all in our last inherited life (from the smallest microbe, to plants and animals and us) requires us to respect and care about our impacts on the Earth. The forces of evolution and survival have not made this planet an always pleasant place, and suffering is everywhere. Life is in a difficult and precarious position, conditions change over time. Those conditions help determine what arises and survives. As conditions change over the aeons to come there is no reason to believe that we will remain or be unchanged. Having adopted an agnostic viewpoint here, on re-birth in the unknowable future, we might re-frame Thích Nhất Hạnh’s words:

"I can see that in a future life I will be a cloud. This is not poetry; it is science.... And I will be a rock. I will be the minerals in the water. This is not a question of belief in reincarnation. This is the future of life on Earth. We will be gas, sunshine, water, fungi, and plants. We will be single-celled beings; and add: We will be human beings."

This is not intended to be an explanation of the buddhist model. That model is pre-scientific. Rather, I have attempted to explore the Buddha’s intuitive model in the context of scientific knowledge. The ideas and practices of Buddha's time seem to remain useful, and the message can remain essentially intact. The use of this updated intuitive model shows us the balance between “nature” and “nurture”. The saṅkhāras (patterns and pattern makers) from the past are in our genes, but also in that which surrounds them. New saṅkhāras are evolved or imposed from conception, through birth and in life. The Buddha’s model shows us that we can to some extent reveal and unwind some of those patterns. People will increasingly find a need to do that as the Earth reacts and society reacts to humanity - we need to recognise the Earth as the only home for life as we know it. There is little prospect of colonising the planets where uniqueness is in everything everywhere. But, we can cultivate ourselves individually by raising awareness of the nature of the mind’s reactions and actions; and collectively through our ongoing interactions. In the long term, we can minimise harm to the Earth, ourselves and other living beings.

References

Batchelor, S 2017, Secular Buddhism: Imagining the Dharma in an Uncertain World. Yale University Press, Kindle Edition.

Bodhi, Bhikkhu 2000, The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: a new translation of the Saṃyutta Nikāya, vols 1 & 2, Wisdom Publications, Boston.

Bodhi, Bhikkhu 2012, The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: a translation of the Aṅguttara Nikāya, Wisdom Publications, Boston.

Buddhaghosa, 2010, The Path of Purification: Visuddhimaga, translated by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu, Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy.

Dawkins, R 1982, The Extended Phenotype, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Epstein, M 1995, Thoughts without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist perspective, BasicBooks, New York.

Ellsberg, & Laity, Eds 2001, Thich Nhat Hanh: Essential Writings, Orbis Books, New York.

Garfield, JL 1995, The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā: translation and commentary, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Gombrich, R 2009, What the Buddha Thought, Equinox, London.

Ñāṇamoli, & Bodhi, 1995, The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: a new translation of the Majjhima Nikāya, Wisdom Publications in association with the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, Boston.

Salzberg, S 1995, Lovingkindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness, Shambhala Publications, New York.

Strawson, G 2006, ‘Realistic Monism: Why Physicalism Entails Panpsychism’, Journal of Consciousness Studies 13 (10-11):3-31.

Wynne, A 2007, The Origin of Buddhist Meditation, Routledge, London and New York.

Web sources

Batchelor, S 2012, “A Secular Buddhism – an essay, published in the Journal of Global Buddhism, which explores the possibility of a complete secular redefinition of Buddhism”, viewed 13 March 2018, https://bodhi-college.org/wp-content/uploads/ASecularBuddhism.doc

Bodhi College “Early Buddhist Teaching for a Secular Age”, viewed 13 March 2018, https://bodhi-college.org/buddhist-articles-videos-links

Secular Buddhism “Foundation for Mindful Living”, viewed 13 March 2018, https://secularbuddhism.com/

Secular Buddhist Association, viewed 13 March 2018, https://secularbuddhism.org/

Smith, D 2018, “Dependent Origination”, Youtube video, viewed 13 March 2018, https://youtu.be/A2cDhGVgb9A

Thanissaro, Bhikkhu 2013, “Cula-Malunkyovada Sutta: The Shorter Instructions to Malunkya”, translated from the Pāli by Thanissaro Bhikkhu, viewed 14 January 2018, https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.063.than.html.

Wikipedia, “Buddhism and science”, viewed 14 January 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhism_and_science